Art, the undefined, unidentified, and inexplicable aspect of human life. Its omnipresence, ironically, has so well placed it along the blind spot. Art is not created on canvas, neither on walls nor is it stroked on paper but it grows in the mind. The hands just obey the neural orders.

Mediums trigger emotions which ignite the human soul, the beauty of perception, and the art of comprehension. One such medium is architecture.

Architecture is built art. The construction techniques might require engineering assistance and certain systems of science but what induces emotion in space is the culmination of elements that define natural art. The play of proportions, the scheme of scales, the bombing balance, and above all the vividity of visuals amalgamate to create what is called the ‘space potion’.

This brings forth the inter-relation of science, art, and architecture. The age-old techniques used by Indians to construct temples involved intricacies of design to focus light, inculcate height patterns to connect to the cosmos, create proportions, acquire acoustics, and propose structural systems that still stabilize the structure. The construction of the temple itself could be termed as a ‘work of art’.

The art of optical illusion was well-adopted in architecture by the Romans in the construction of the Pantheon. The technical angles (via concepts of the golden ratio) inculcated to create visual disparities proved in favour of the ingenious optics and hence enhanced the beauty of architecture.

Artistic expression is used to develop a dialogue between the space and the user, to which art and architecture combined can give a new dimension. Architect Daniel Libeskind builds this connection as the user lurches along the alleys of the Jewish Museum. The trail through the extremely heightened walls triggers Holocaust horrors inside the users with the only ray of light literally stranding out from the last-chamber slit. And so emotions expand the architectural character of a space.

Architecture, as misunderstood by many, is not just a medium to stimulate aesthetic and emotional stimuli but as a tool to solve user problems, creatively. Le Corbusier, the famous Swiss-French architect, proposed the creation of CIAM post World War 2 to cater to Europe’s critical housing conditions. The Unite d’ Habitation building was a unique outcome, introducing the world to the modern era high-rise, mixed-use building category.

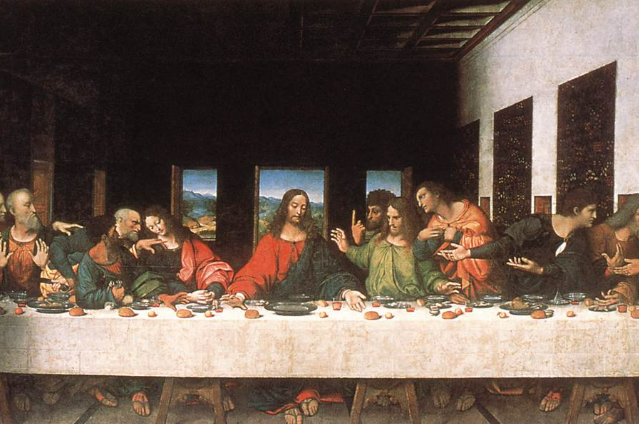

Renaissance, the age of enlightenment, empowered not just world politics but also touched the arenas of art. In terms of art and architecture, Renaissance marked a shift from art for the aristocrats to art for the people. In fact, the paintings portrayed a technical maturity with the discovery of perspective as an obvious observation.

Image by wikipedia.org

According to the famous renaissance artist, Leonardo Da Vinci, if nature, God’s creation is mathematical, proportionate, and symmetrical, then man-made creations ought to be so too. Da Vinci took this to heart and strived to create balance in his works including paintings, sculptures, and architecture. This particular artistic aspect is what adorned the architecture of the period. The intricacy and deep heed paid to the calculative construction of various elements of architecture was supremely proportionate and well in ratio. Hence, most of the renaissance buildings have balance and symmetry as basic defining traits. A careful look at Da Vinci’s works, Mona Lisa and The Last Supper reveal complete balance and symmetry admiring the golden ratio. The buildings his sketches depict present a keen study of optics beautifying illusion in spaces. The play of light and shadow reveals the artistic angle of spaces. Similar to his paintings, principles of symmetry and proportion adorn his perception of architecture. In Leonardo’s words, “Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses- especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”

Monalisa;

Image source: Wikipedia

Image source: Wikipedia

There is a basic yet very interesting trait that time possess, its attitude to change and so does people’s perception and hence the art.

The Industrial Revolution marked a drastic transformation. With rationality at its peak, people lost the eye for art. The cities were trailed via stinking streets leading to dingy dwellings. Buildings constructed were mainly industrial, lacking any source of ventilation, light, or nature. This not only created physical illness for people but also induced injuries like depression. Since people weren’t healthy, it was clearly not rational going with the flow.

Hard Times, the famous novel by Charles Dickens expresses, “Some persons hold”, he pursued, still hesitating, “that there is wisdom of the head and that there is a wisdom of the Heart.” It became the responsibility of art enthusiasts to revive its lost glory but with a modern touch.

Architecture grew as the sole hope of the world especially post-World War II. The war displaced many and drastically altered the socioeconomic conditions. Hence the issue of mass housing came in front of the governments across Europe which was eventually resolved by great architects.

The functionality of the building became a prime factor, an un-compromisable aspect. But the merging of aesthetics could also not be avoided. Hence architecture was introduced to the beauty of minimalism. Heed was paid to basic requirements, the optimum sizes and dimensions in terms of both spaces and their demeanor. The ribbon windows of Villa Savoye by Architect Le Corbusier, provide good ventilation for the in-mates in addition to framing views of the nearby sightful sites and solemnly enhancing the façade features.

Soon art became an inseparable component of architecture. Buildings gained aesthetic essence based on their functionality. The spiral ramp (and hence the external form) of the Guggenheim Museum, USA fulfills the fact. Architect Frank Llyod Wright maintained the purpose of the place but applied his art knowledge hence creating an aesthetically legible space. Henceforth modernism gifted architecture the counterpart of what anciently existed as heavy ornamentation.

Image Source: Unsplash.com

The splash of modernism in the west had its sprinkles experienced in Asia as well. A land initially adorned with warmth and colour, found itself in grey. The bright, versatile, interactive spaces ‘developed’ to a more confined, private, stay-inside sophistication. India experienced this transformation during and post the colonial conquer. The Britishers initially and later the upper class started imitating the West in terms of both art and architecture. What was actually required was not imitation but inspiration. This realization gave rise to a concept called Critical Regionalism. Critical regionalist architects were known to merge the locale with modern. Considering the local climate, material, context, and socials, the architects try to fuse it with the principles of modernism ultimately creating a structure that is contextually accepted and contemporarily sound.

India has had two great architects who dwelled on this philosophy. Architect B.V. Doshi and Architect Charles Correa. Doshi’s Amdavad-ni-Gufa is a beautiful blend of art and architecture. The underground, cave architecture-inspired structure serves as M.F. Hussain’s art gallery; one which challenged Hussain to have a canvas-less display of his artworks. The Gufa strolls aside the Architecture College, CEPT, again designed by B.V. Doshi, and presents an amalgamation of two creative genius.

Image Source: https://www.sangath.org/

Entitled as the ‘Greatest Architect of India’ Charles Correa possessed a modern approach towards Indian architecture. He successfully tried to shape the teachings of modernism suitable to the Indian context. The Jaipur-situated Jawahar Kala Kendra designed by Correa conceptualizes the unique planning grid of the city of Jaipur to form the plan of the Arts and Cultural Centre. The perfect nav-greha mandala plan of the city finds a block displaced strategically due to the presence of Aravallis. Inspired from this, the plan of Jawahar Kala Kendra has one block (out of nine) arbitrarily placed symbolising the kinship with the city. But was is the most striking feature is the central courtyard with an open-air theatre for public interaction, all under the open sky. A signature of Correa’s design, the open-to-sky spaces define his philosophy. In one of his essays, Correa quotes, ‘In India, the sky has profoundly affected our relationship to built-form, and to open space. For in a warm climate, the best place to be in the late evenings and in the early mornings, is outdoors, under the open sky.’

That is how art smoothly enters into architecture; with spaces that flow seamlessly arising user emotions, fulfilling user needs, and enhancing user experience. It need not always be loud to sound extravagant, a soft whisper is powerful enough to trigger the heart.