Introduction

“A good dinner is of great importance to good talk. One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well”, writes Virginia Woof in A Room of One’s Own. This paper is inspired from, and is an extension of this basic idea, i.e., proper food is as much a woman’s right as it is man’s. But, even today we see the disparity between the health conditions of a man and a woman. A Forbes India article released in October 2018 mentioned that above 80% of Indians are protein deficient and among them, women consume 13% lesser protein than men. Even though the standard of protein requirement of a man and a woman is the same. An adult should ideally consume 0.8 grams of protein per 1 kg of body weight; pregnant and lactating mothers should consume more. However, the general reality is far from this and the condition of women belonging to rural areas and marginalised communities is far worse.

Besides this, Anaemia is another nutritional deficiency that haunts the women of India, and is a major contributor in maternity deaths. It is caused by the deficiency of iron in the body. Young children, women in the reproductive age group, pregnant and lactating mothers are more susceptible to it.

“Disappearance of biodiversity on farms is linked to disappearance of women from farms. This is food insecurity for the girl child. Malnutrition in childhood leads to malnutrition in adulthood. Anaemia is the most significant deficiency women suffer from. Anaemia is also the most significant reason for maternal mortality. When underfed girls become mothers, they give birth to low-birth-weight babies, vulnerable to disease and deprived of their right to full, healthy, wholesome personhood” (Shiv 25).

According to the Global Nutrition Survey of 2016, India ranks at 170 among 180 countries for anaemia among women. Witnessing the deteriorating state of women with respect to anaemia, the flagship initiative The National Anaemia Prophylaxis Programme was established in 1970 to distribute Iron and Folic acid tablets. However, even after all these years the state hasn’t improved at all, in fact has gotten much worse in select places. The National Family Health Survey of 2019 reported that a whopping 68.4% children and 66.4% women surveyed, suffered from anaemia. This shows that our solution to women’s health issues is not only ineffective but also ill informed. Recent scholarship in the area of Feminist Food Studies unearthed different relationships of women with food that reflect a deep-seated sexist and patriarchal prejudice against women. Many scholars posit the blame on the extremely tiresome lifestyle of women where they perform a variety of chores, both inside and outside the home. This coupled with a nutrient-poor diet results in adverse health conditions for women which is carried over from one generation to another. The solution to these problems doesn’t lie in thinking about a novel solution but in pondering over these problems and questioning the socio-cultural practices that are the causes behind these problems.

Today, we live in a world where the ‘capital’ reigns supreme. It tethers itself to any and every ideology that helps it grow. While nutritional deficiency-based diseases may be more common among rural women and women belonging to other backward sections of the society; middle class women and women of the metropolis deal with a different version of a similar problem. Urban women are obsessively catering to the unrealistic standards of beauty. When looked at from a feminist perspective, ‘Food’ no longer remains just a source of sustenance.

It finds itself at the intersection of the complex web of racial, cultural, and gender relations that are themselves influenced by the socio-economic conditions. Choosing to critically look at food in its various stages (production, distribution and consumption), through a feminist perspective is an attempt to uncover the structural inequalities and various other discriminatory practices pertaining to food, that go unnoticed.

“Hunger and obesity (or the fears of it) are feminist issues both because their worst victims are women and girls, and also because they are result of a food system shaped and controlled by capitalist patriarchy” (Shiv 25).

In this paper, we have tried to critically engage with the processes of food production, food insecurity, along with food practices, from an intersectional feminist perspective that uncovers the food and food habits as markers of patriarchal prejudice. The aim of this paper is to carry out a qualitative analysis of women’s relationship with food as producers as well as consumers. We have tried to substantiate our points by taking examples from daily personal lives of women and also its representation in mainstream media.

Gendered Division of Food and Labour

The gendered division of labor in which men strive, compete, and exert themselves in the public sphere while women are cocooned in the domestic arena. Narayan posits that the common practice of barring Indian women from waiting tables in the public space of Indian family-owned restaurants, though they are often permitted to work behind counters of family grocery stores, may be because the serving of food is associated with the maintenance of that distinctive spiritual “essence” since it takes place within the “intimacies of Indian family life”.

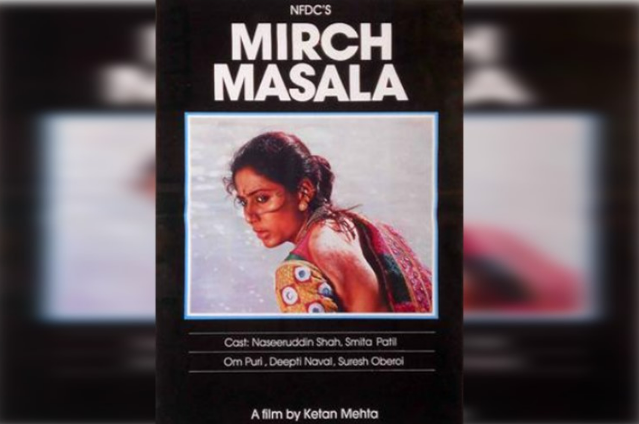

The kitchen is a location where women ‘perform gender’ all the time. Women on the Indian subcontinent are socialised to believe that the kitchen is where they should find their identity, reinforcing the notion that the kitchen is actually a gendered area. Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala is a radical critique of food production and the gendering of the bodies involved in bringing food to the table.

“Mirch Masala has provided feminist filmmakers and cultural brokers much critical fodder to negotiate how sites of food production—be they in the restaurant kitchen, or within the walls of factories—are gendered. From its onset, the film announces itself as being fundamentally about land, people, and labor” (Mannur 120).

In one of the scenes in the movie, when mukhi’s wife Saraswati (Deepti Naval) comes to know about the women trapped inside the spice factory without food. She takes it upon herself to cook for them. When she takes the rotis and offers it to Abu Mian (Om Puri), she provides a means of sustenance to the women taking refuge inside the factory. Upon receiving the package of rotis, the women express their gratitude, remarking that only a woman would think to bring roti during a crisis. Saraswati’s work remains invisible, she is never credited or paid for the work that she does except in the instance mentioned above. Mukhi (Suresh Oberoi) comes home only to eat or bath, everything in the house by his wife.

“Through the work of feeding, “women quite literally produce family life from day to day”. DeVault maintains that this work of feeding is invisible as work and, though it is central to the construction of family, women themselves often deny that it is work” (Haber 9).

The women are allowed to work in the spice factory because it fits into the gendered norm of kitchen duties. Despite the fact that the women labour in a factory, their work is not valued, as evidenced by the interaction between Subedar and Jeevan Seth (factory owner).

Still of Smita Patil from Mirch Masala

Image by Imdb.com

“Subedar: Do you own that spice factory?

Jeevan Seth: It’s not really a factory. They call it that jokingly. It just provides meagre work for a few poor women” (Mannur 121-122).

Because it employs women, Seth does not believe it to be a factory. He sees it as a charitable act that provides sustenance for the poor women. Women's labour is thus not considered work even outside of the family and kitchen.

Another point to note is that the food consumed by these women is extremely low in nutrients. They're eating roti with onion and pickle. The food is less nutritious because it was made for women. The film is set in colonial India, where gender norms were severely enforced. Because they undertook physical labour, the male members of the family were given nutritious food. Women, on the other hand, were assumed to do no such physical labour because housework was invisible, therefore their meals consisted of leftover food. We look into a detailed analysis of secondary status of women’s food in the next part of the paper.

In contemporary society, there also appears to be a lack when it comes to women eating in movies and commercials. The image of a man eating is common, while the image of a woman eating is not. In commercials, male eating is inextricably tied to female offering of love. This concept may be seen in the advertising for Everest and Fortune oil. In the Everest commercial, we see the onus of cooking food falling upon the women. In the advertisement, there is no father figure, which is analogous to the lack of a male figure in the kitchen. In these spice adverts, the women are always shown to be exceedingly happy and satisfied. “Women aspire to run households without feeling that it is a burden. She argues that these images construct gender by depicting “kitchen work as ‘naturally’ rewarding to women both emotionally . . . and aesthetically”” (Haber 14). Everest's tagline, ‘Taste main best Mummy aur Everest,’ plainly emphasizes that cooking is a gendered duty that should preferably be performed by women.

“In the necessity to make such a division of labor appear we find another powerful ideological underpinning…for the cultural containment of female appetite: the notion that are most gratified by feeding and nourishing others, not themselves” (Bordo 118).

Traditionally, these advertisements end with a woman looking contentedly at her family, who are eating the food she has prepared. It is suggested that women receive their gratification through nourishing others. She is never shown to be eating the food. Even outside the familial construct, it is always the woman who is shown as doing the cooking. In Fortune Kachchi Ghani Mustard Oil ad, we see politicians sitting together and eating. The commercial starts with a close-up shot of a male politician devouring his food.

“Men are supposed to have hearty, even voracious, appetites. It is a mark of the manly to eat spontaneously and expansively, and manliness is a frequent commercial code for amply portioned products: “Manwich,” “Hungry Man Dinners,” “Manhandlers.”” (Bordo 108).

Though the female politician is sitting on the same dining table, there isn't a single shot of the female politician eating anything. The male politician is offered bhindi curry which he initially refuses, but takes it later on the insistence that the curry was cooked by the female politician. It shows a man consuming food made by a woman, as per traditional gender roles. Almost every commercial that features men eating features a woman in the background preparing the food. Women are expected to prepare food and not eat it excessively. Susan Bordo talks about this idea in terms of replacing Berger’s formulation of ‘Men act, and women appear’ with ‘men eat and women prepare.’ It is always the women who are shown as preparing food in these commercials. If ever there is a male figure present in the kitchen, he is depicted as an exception not as the norm.

If we look at the idea of ‘men eating and women preparing food’ in an urban social milieu. The kitchen then becomes a site of oppression. Because most of the women in this cultural setting do not have the power to walk away from the kitchen. In Ritesh Batra's The Lunchbox, Ila (Nimrat Kaur) is unable to leave her husband, Rajeev (Nakul Vaid), despite her dissatisfaction with her marriage. Rajeev, like the other male characters in the commercials, does not participate in housework.

Food is equated with maternal and wifely love throughout our culture. There is also the prevalence of the cultural idea that a women’s marriage might depend upon good home cooking. Ila tries to save her failing marriage by cooking new recipes for her husband. Food becomes an act of appeasement towards her partner. Rajeev, on the other hand, expresses his dissatisfaction with Ila's food, claiming that it falls short of the nutrition standards that she is expected to provide. The notion that the woman has to care for her man and provide her nutritious food is evident in Rajeev’s claim. Thus, building on the idea that women herself should have less nutritious food and provide more nutritious food to her husband (male members). Rajeev's perspective conforms to the widely held belief that women are food producers rather than consumers.

Women as Producers of food

“From seed to table, the food chain is gendered” (Shiv 17).

Conventionally, women have played a varied role in the production of food. As farmers they cultivate crops and then in a family, they play the role of nurturers by cooking and providing sustenance for everyone. However, there is no acknowledgement of this labour. Somehow, a woman’s work is reduced to the status of “assistance” for a man’s work and therefore, becomes invisible. Based on a report published by the international humanitarian group OXFAM, nearly 75% of the full-time workers in Indian farms are women.

“Agriculture has been evolved by women. Most farmers of the world are women, and most girls are future farmers. Girls learn the skills and knowledge of farming in the fields and farms. What is grown on farms determines whose livelihoods are secured, what is eaten, how much is eaten, and by whom it is eaten” (Shiv 19).

Around 60%-80% of the food is produced by female farmers yet their labour goes unaccounted for. A woman’s labour is dubbed as many things- a token of love, duty, etc. What is interesting to note is that even though a woman’s labour is venerated to a position of selflessness, it never actually is valued enough to be given appropriate remuneration in the form of wages. Ecofeminist Vandana Shiva writes in her essay Women and the Gendered Politics of Food:

“There is a conceptual inability of statisticians and researchers to define women’s work inside the house and outside the house (and farming is usually part of both). This recognition of what is and is not labour is exacerbated both by the great volume of work that women do and the fact that they do many chores at the same time. It is also related to the fact that although women work to sustain their families and communities, most of their work is not measured in wages” (Shiv 19).

In spite of the significant number of women engaged in agriculture, only a meagre number of around 13% of them own land. Since, most of the land and property in India is transferred through inheritance, women remain mere labourers (unless they are employed at someone else’s farm in which case get a lesser wage than their male counterparts) for generations after generations, despite the Equal Inheritance Rights to Ancestral Property Act of 2005. Additionally, a woman demanding for her share in her father’s property is subjected to a lot of slander and cultural stigma, as patriarchy deems it, a son’s right to inherit the father’s property.

In the Indian context, the woman is often associated with the ideal of Annapurna. Annapurna, according to the Hindu mythology, is an incarnation of goddess Parvati and is known as the goddess of food. She is seen as a symbol for nourishment and care. The Indian women (mostly Hindu women) are equated to the status of Annapurna, where it is thought that she derives contentment from feeding her loved ones before her. Not to mention, many women themselves have bought into this trope and do not hesitate from feeding their family members better and more food, sometimes at the cost of their own debilitating health conditions. The appropriation of Annapurna is not only limited to food consumption, it extends to the standards set for a woman’s role in the kitchen. A woman’s tireless and monotonous work in the kitchen is termed as “labour of love” and therefore, is never seen as “work”.

Women as Consumers of food

Food consumption practices of women are deeply embedded within conventions, beliefs and stereotypes that are shaped by the dominant cultural and economic standards. Patriarchy finds itself manifested in almost all shapes and forms, in all of them. It has been amply documented that women in India suffer from nutrition deficiency more than men. This nutrition deficiency arises from different cultural practices imposed upon women in this country. We know, for example, that caste Hindu women serve as both symbolic and literal providers of food (Annapurna) rather than food consumers. The women in orthodox (and even not-so-orthodox) caste Hindu households are associated with cooking and serving rather than eating. The structure of meals is such that men and children are served first, and men receive the best portions, while the women who cook and serve the meals make do with whatever is left over. Neither them, nor the family, actively puts their nutritional needs as a priority. In fact, a lot of interviews have revealed that women find satisfaction in sustaining themselves with the least and providing the best for their family members.

Taking cognisance of the deplorable nutritional standards of women (mostly rural) in India, when the central and state governments introduce programs under which pregnant and lactating mothers are provided with nutritional supplements like multi-grain cereal powders, eggs, etc., they almost always feed it to their children or other family members saying that they need it more than them.

“In a study of rural poverty, nutrition, and the bias against female children, Amartya Sen has suggested that increasing rural family income may not suffice to remedy the deprivations of the female child; ‘direct nutritional intervention through supplementary feeding’ is necessary to compensate for familial (including maternal) biases in favour of male members” (Roy 393).

A go-to justification for this is that men go out to work, they need more if not better food. But as we have already addressed in the beginning of this paper, women do as much labour as men. Additionally, they bear children too which is a huge strain on their bodies and their reproductive health. Women with nutrition deficiency during their pregnancy give birth to children who are susceptible to diseases and have stunted growth. The rate of child and mother’s mortality is highly dependent on their food consumption patterns during their pregnancy.

Women, too, have hierarchies, with the youngest daughter-in-law, widows, and poor female relatives at the bottom of the gastro-political ladder. Also, women are prohibited from eating certain types of food like milk. They are kept for their male counterparts. This secondariness at mealtimes, combined with women's observance of fasts and other types of alimentary asceticism, as well as the severe dietary privations of caste Hindu widows, has ensured a visible but often unremarked position for hunger in their daily experience.

“Providing a sophisticated and complex version of we are what we eat, Lupton identifies “food and eating... [as] intensely emotional experiences that are intertwined with embodied sensations and strong feelings... central to individuals’ subjectivity and their sense of distinction from others”” (Haber 16).

The secondary nature of food eaten by women, then, becomes a depiction of secondary status of existence in Indian families. Dr Vibhawari Dani, former senior Professor of Pediatrics, Government Medical College, Nagpur, says “The secondary status of women in our cultural fabric results in the girl child receiving secondary treatment, lowering her confidence. Discrimination being shown in her education, thereby affecting her personality lifelong and malnutrition per say in childhood” (Sawant). A bias toward male child has been identified in several studies, which not only contributes to female infanticide but also to the neglect of female child in the household. Their malnutrition is directly related to their gender. There appears to be a higher risk of women giving birth to undernourished children when teenage girls have a low Body Mass Index. Widespread malnutrition among mothers feeds a generational cycle of malnutrition in children. Girls who are malnourished grow up to be malnourished women who give birth to a new generation of malnourished children.

Women's food consumption is influenced not just by their household's economics, but also by the dominant diet culture. Because of religious rituals, the concept of fasting has always been widespread in Indian households. Fasting, which is frequently done by women, restricts their eating habits. On various days of the week, they were not allowed to consume meat. Some fasts compelled them to go without food (or only eat once) for the entire day. The concept of fasting has religious roots, but today's diet culture is built on beauty standards. It is strictly adhered to in order to acquire the slim and slender body ideals.

Diet Culture

Heidi Hartman, in her essay The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism: Towards a More Progressive union, talks about how the modern-day patriarchy has formed a symbiotic relationship with capitalism. They benefit from each other. In such a scenario, changing trends in beauty and lifestyle are great opportunities for companies to introduce new products into the market that will increase consumption. The ‘happy marriage’ of Capitalism and popular Feminism can be seen in the prevalence of Diet culture in the society.

“Diet culture— or capitalism in general— demands that we purchase products to help us lose weight so that we will overconsume products that might lead to weight gain; this is one the paradoxes of dieting” (Gailey 67-68).

The “diet-culture” appears to be a similar opportunity that has made the anxieties and vulnerabilities of people regarding their body a fertile ground for pushing all kinds of products that are inclusive of but not limited to “healthy food options”, diet plans, synthetic pills, etc. It operates by dictating that people avoid eating sugar or foods high in fat or carbohydrates most of the time, but if they have “been good” and stuck to their diet, then they deserve to “splurge” on occasion. We see diet culture regulating women's bodies but also aiding Capitalism's cause by encouraging women to spend money on both dietary products and food delicacies. “In the United States of America itself, the commercial diet industry manages to create a revenue of approximately $60 billion, annually” (Contois 124). The “health and beauty” industry is deeply rooted in promoting the extensive consumption of commodities, in the form of food, clothing, makeup, and more. The current definition of “health” is expressed only in terms of appearance.

“The bourgeois “tyranny of slenderness” (as Kim Chernin has called it) had begun its ascendancy (particularly over women), and with it the development of numerous technologies – diet, exercise, and, later on, chemicals and surgery – aimed at a purely physical transformation” (Bordo 185).

The Snickers commercial depicts men turning into ‘heroines’ when they are hungry. Heroines are supposed to follow a strict diet routine and are therefore always hungry. The advertisement seems to be a depiction of the perennial hunger in women forced upon them by the patriarchal constructs. These actresses who adhere to a stringent food routine are the ideal of female beauty. This instils in women a desire for thinness in general.

“A desire for thinness, Bordo holds, is a logical response to the West’s “historical heritage of disdain for the body”. The second axis is the desire to control this alien body. Unable to control other aspects of their lives, women go to extreme measures to control their bodies through dieting and exercise, gaining a sense of accomplishment by their ability to achieve a perfect body, bending their bodies to their wills, gaining mastery over their bodies” (Haber 21).

This idea of controlling a woman's body can be seen in many Indian advertisements. In Lipton Green Tea commercials, it is always the women who are shown to be in need of reduction of fat (belly fat). “Advertisers are aware, too, of more specific ways in which women’s lives are out of control, including our well-documented food disorders; they frequently incorporate the theme of food obsession into their pitch” (Bordo 105). The commercial shows numerous women hiding their fat especially when in presence of a male figure. In their quest to achieve a ‘perfect’ body, women are drawn towards the idea of compulsive dieting or using products which help them reduce fat. The image of female attractiveness in the contemporary world is that of a slim and slender body.

For women, this slender body becomes a source of empowerment. It embodies qualities such as self-control, self-containment, and self-mastery, which are all highly valued in modern society. Kim Morgan discusses her obsession with slenderness, which led to anorexia, in the documentary The Waist Land:

“It was about power…that was the big thing…something I could throw in people’s faces, and they would look at me and I’d only weigh this much, but I was strong and in control, and hey you’re sloppy.” (Bordo 209-210).

Susan Bordo in her essay Anorexia Nervosa talks about the fear of ‘getting fat’ in our culture. She describes the body to be an instrument and medium of power. The slender body of Kim Morgan in the above example gives her power and control in the society.

“Susan Bordo also focuses on the cultural meanings of the prevalence of eating disorders among women, theorizing that anorexia nervosa is the “logical (if extreme) response to manifestations of anxieties and fantasies fostered by our culture”. Maintaining that the “natural” body is a fiction, Bordo takes a social constructionist perspective to the body, including in her analysis the effects of both patriarchy and white supremacy” (Haber 21).

Many anorectics remark about having a 'ghost' inside them, according to Hilde Bruch, a psychoanalyst who has worked extensively on eating disorders. She states that the other self of the anorectic is invariably male, preventing these anorectic women from eating. In the commercial for Safola Masala Oats, a woman is seen refusing to eat. Despite the fact that the woman does not need to be on a strict diet, we observe her denying herself samosas. In the same commercial, the masculine character is shown devouring his food once again. A man is depicted presenting food to a woman in another advertising, but she just takes a small taste. The commercial continues to portray the woman eating very little to preserve her slender figure, despite the fact that she is already pretty slim. It's possible that the woman in these adverts has Anorexia Nervosa. These businesses target women's anxieties and eating problems in order to sell their products. The product is portrayed as a way for women to maintain their slenderness even after they have consumed it.

“The proper diet, the right amount of exercise and you can have, pretty much any body you desire,” (Bordo 247).

Women's anxieties about their bodies are exploited by consumer culture, which targets them with dieting products. Angela McRobbie in her essay Young Women and Consumer Culture:

“The emerging post-feminist language of personal choice, freedom and independence which the magazines of the 1990s endorsed. Likewise, the emerging codes of sexual freedom and hedonism ought to have been understood as manifestations of new technologies of the self which once again secured the youthful female subject in designated ways according to a limited (or expansive) range of legitimate desires and pleasures” (McRobbie 538).

Consumption and technology of the self, according to McRobbie, intensify postfeminist sensibility. Supplements, weight loss surgery, weight loss workout routines, and clothing such as shapewear have all become the norm of femininity. In the contemporary world, the thin ideal is popularised not through magazines but through modern social media apps like Instagram, etc. Weight loss journey accounts that track changes, 'fitspiration' accounts that document food diaries and exercise routines, weight loss 'before and after' images, and the promotion and commercialization of weight loss products and supplements are just a few examples through which Instagram controls the thin ideal.

Instagram also promotes diet culture through celebrities and influencers. After you've clicked on it once, Instagram's algorithm tries to keep showing you these diet profiles and posts. The consumerism of diet culture can also be seen in Instagram’s ‘targeted adverts.’ Women's self-surveillance has increased as a result of the emergence of apps that slim your body and alter your appearance. The use of Instagram filters by users is an extension of the platform's diet culture. Instagram is a surveillance tool that has altered the politics of appearance. Instagram's gender dynamics mirror the gender dynamics of diet culture in general. Previous research has indicated that the characteristics of diet culture, such as weight loss dieting, are disproportionately directed at and undertaken by women than men.

The cyclical nature of dieting in women's life is reinforced by Instagram as a platform for diet culture. Because of Instagram's addictive quality, users are constantly drawn back to it, and therefore to diet culture. Instagram's visual imagery fosters comparison and evokes sentiments of guilt and shame. Body image, self-esteem, and overall emotional and mental well-being all suffer as a result.

Conclusion

“The methods of inquiry that we use to analyse social and material life must begin at the everyday level of lives, but also attend to structures that shape them” (Smith 1987).

Food, as a cultural marker, is so plural in its significations that it seems like an apt tool with which we can move beyond a homogenous and generalised analysis of prejudices against women, to a more nuanced, intersectional and localised one.

“The recent scholarship on women and food conclusively demonstrates that studying the relationship between women and food can help us to understand how women reproduce, resist, and rebel against gender constructions as they are practiced and contested in various sites, as well as illuminate the contexts in which these struggles are located” (Haber 2).

Food practices, be it related to the cultivation, purchase or cooking of food, or the food habits of women are a representation of people’s individual lives in a particular milieu. Two women, living in the same locality, falling under the same class bracket would still have starkly different relations with food because they might belong to different religions or castes. Not only the kind and quantity but also the manner in which food is eaten, viewed, and represented in certain cultures can tell us a lot about their inherent beliefs. Elspeth Probyn, a scholar in Gender and Cultural studies says, “bodies eat with vigorous class, ethnic and gendered appetites, mouth machines that ingest and regurgitate, articulating what we are, what we eat and what eats us” (Haber 16).

“Citing race, class, gender, and sexual oppression in the society and the abuse of women and girls in families as important causes of eating problems, she maintains that eating problems will be cured only when the society cures itself of injustice” (Haber 21).

This essay on women and food tackles the fundamental questions that women's studies highlighted earlier, providing new insights into both women's lives and the environments in which they exist.

. . .

Works Cited:

- Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. London: University of California Press, 2003.

- Contois, Emily. ““Lose Like a Man”: Gender and the Constraints of Self-Making in Weight Watchers Online.” Feminist Food Studies: Intersectional Perspectives. Ed. Jennifer Brady, Elaine Power, and Susan Belyea Barbara Parker. Toronto and Vancouver: Women's Press, 2019. 123-144. Digital File.

- Gailey, Jeannine A. The Hyper(In)Visible Fat Woman: Weight and Gender Discourse in Contemporary Society. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. Digital File.

- Haber, Arlene Voski Avakian and Barbara. “Feminist Food Studies: A Brief History.” From Betty Crocker to Feminist Food Studies: Critical Perspectives on Women and Food. Ed. Arlene Voski Avakian and Barbara Haber. Amherst & Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005. 1-28. Digital File.

- Mannur, Anita. Culinary Fictions: Food in South Asian Diasporic Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010. Digital File.

- McRobbie, Angela. “Young Women and Consumer Culture.” Cultural Studies 22.5 (2008): 531-550. Web. 15 June 2022.

- Roy, Parama. “Women, Hunger, and Famine: Bengal, 1350/1943.” Women of India: Colonial and Post-Colonial Periods. Ed. Bharati Ray. New Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilization, 2005. 392-426. Digital File.

- Sawant, Chitra. Secondary status to women affects kids’ overall growth. 31 May 2019. Web. 15 June 2022.<www.freepressjournal.in/mumbai>.

- Shiv, Vandana. “Women and the Gendered Politics of Food.” Philosophical Topics 37.2 (2009): 17-32. Jstor. 6 June 2022. <www.jstor.org/stable/43154554>.