1. Introduction

On a vibrant morning in January 1950, India embarked on a monumental journey as it adopted its Constitution, a document that would serve as the bedrock of its democracy. With the stroke of midnight, the nation transitioned from colonial rule to self-governance, enshrining the values of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity. The Constitution not only laid the framework for governance but also established fundamental rights that would empower citizens and protect their dignity. As we celebrate 75 years of this living document, we reflect on its profound impact on the social, political, and cultural fabric of India, a testament to the resilience and aspirations of its people.

2. Historical Context

The Indian Constitution, adopted on January 26, 1950, stands as the cornerstone of India's democracy. As the nation celebrates 75 years of this remarkable document, it is essential to examine the historical context that led to its creation. The need for a constitution didn’t arise suddenly with the end of British colonial rule; rather, it was shaped over centuries, influenced by ancient traditions of governance, the abuses of colonial rule, and the aspirations of a newly independent nation.

1. Pre-Colonial India: The Foundations of Governance

Before British colonization, India had a rich tradition of governance systems that were diverse, complex, and deeply rooted in social, cultural, and religious contexts. Ancient India witnessed various systems of governance, from the republican states of the Mahajanapadas (6th century BCE) to the highly centralized monarchical structures of the Mauryas and Guptas.

- Ancient Republics and Monarchies: The Mahajanapadas, such as the Lichchhavis and Shakyas, practiced forms of democracy, where local assemblies had significant power in decision-making. These early democratic institutions, though small-scale, served as the foundation for the later demand for self-rule.

- Dharma and Kingship: Governance in ancient India was also influenced by Dharma Shastras, which outlined the moral and legal duties of rulers. In Manusmriti, for example, the king was seen as a protector of justice and social order, subject to the laws of dharma (righteousness).

- Medieval India: During the Mughal era, India experienced centralized, monarchical rule. Rulers like Akbar established systems of governance that incorporated local traditions with Islamic laws. The Mughal Empire also saw a formalization of land revenue systems, administration, and a central bureaucracy, laying down administrative blueprints for future governance.

While these systems were diverse, they did not foresee the need for a written constitution. Governance was based on personal authority, customs, and traditions rather than codified laws or documents.

2. The Advent of British Colonialism

The arrival of the British East India Company in the early 17th century marked the beginning of profound changes in India’s political landscape. Over the next two centuries, India gradually transformed from a patchwork of kingdoms to a centralized colony under British rule.

- The British System of Rule: The British established a system that focused on centralized control and the extraction of resources for colonial benefit. Laws, such as the Indian Penal Code (IPC) (1860), the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) (1872), and the Indian Evidence Act (1872), were imposed by the British to serve their colonial interests, rather than the needs of the Indian populace.

- The Doctrine of Lapse: The British also introduced the Doctrine of Lapse, which enabled them to annex states if the ruler had no direct heir. This created political instability and resentment among the Indian nobility and public, underscoring the arbitrary and autocratic nature of British rule.

Exclusion of Indians from Governance: Despite the creation of some legal structures, there was no attempt to involve Indians in the legislative processes. The British governance system remained largely elitist, and despite the growing numbers of educated Indians, political power was held firmly by the British.

3. The Rise of Indian Nationalism

The lack of political representation, coupled with economic exploitation, fostered a deep sense of injustice among the Indian populace. Throughout the 19th century, Indian thinkers, intellectuals, and reformers began to demand greater rights and self-governance.

- The Indian Renaissance: Figures like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, and Swami Vivekananda spearheaded social reforms that challenged traditional structures, advocating for greater inclusion, education, and equality. These reforms laid the foundation for a broader movement for self-determination.

- Formation of the Indian National Congress (INC): The creation of the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1885 was a turning point. Initially formed as a platform for educated Indians to voice their concerns within the colonial system, it gradually began to demand political rights. By the 1900s, the INC had moved from moderate petitions for self-rule to a more radical demand for self-government.

- Partition of Bengal (1905): The British decision to partition Bengal as a means to divide and rule further galvanized Indian opposition. The divide-and-rule policy led to widespread protests and a stronger push for independence. Leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak began demanding complete self-rule (Swaraj).

4. The Failure of British Constitutional Reforms

In the early 20th century, the British government began introducing reforms to address some of the demands of Indian leaders. However, these reforms were designed to preserve British control and maintain the colonial status quo.

- Morley-Minto Reforms (1909): These reforms introduced limited self-governance by allowing Indian representatives to join the legislative councils. However, the overall control remained with the British, and the reforms failed to satisfy Indian demands for full political autonomy.

- Government of India Act (1935): Perhaps the most significant of the British reforms, the Government of India Act of 1935, promised a federal structure and greater powers to the provinces. However, it still maintained British control over key areas such as defense, foreign affairs, and communications. The Act created a semblance of self-governance but fell short of granting India full autonomy.

- The Demand for Full Independence: By the 1930s, the INC, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, had shifted from seeking self-government to demanding full independence. The Salt March (1930) and the Quit India Movement (1942) were emblematic of this growing national movement for complete freedom from colonial rule.

5. The Impact of World War II and the Crumbling British Empire

The end of World War II in 1945 marked a significant shift in global politics. The British Empire, exhausted by the war, was unable to maintain its colonies, including India.

- The Quit India Movement (1942): The movement was a final, bold call for British withdrawal. Although it was suppressed violently, the movement highlighted the broad-based demand for independence among the Indian population.

- Post-War Recession and Global Changes: The British, weakened by the war and facing increasing pressure from the United States and Soviet Union to decolonize, could no longer ignore the demands for Indian independence. The Labour government in Britain, elected in 1945, was more sympathetic to the cause of Indian independence.

6. The Formation of the Constituent Assembly: Drafting the Constitution

With India’s independence imminent, the British government agreed to a transfer of power. In 1946, the Constituent Assembly was formed to draft the Constitution for independent India. It was a pivotal moment in the nation’s history, as it represented the collective will of the Indian people, regardless of their diverse linguistic, cultural, and religious backgrounds.

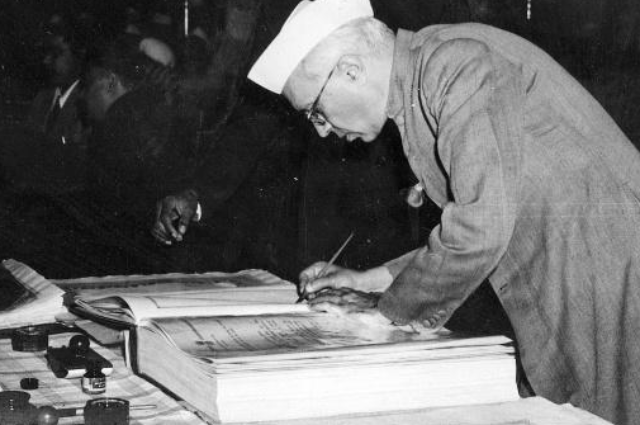

- The Role of the Constituent Assembly: The Constituent Assembly included leaders from all regions and communities. Its members included Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Dr. B.R.

- Ambedkar, Maulana Azad, and Rajendra Prasad, among others. They were tasked with framing a constitution that would ensure democracy, justice, and equality.

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and the Drafting Process: Dr. Ambedkar, as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee, played a crucial role in shaping the Constitution. He emphasized the need for social justice, the abolition of untouchability, and the protection of minority rights. The Indian Constitution became a beacon of hope for marginalized communities, including Dalits, women, and tribal populations.

- The Final Document: After extensive debates, revisions, and consultations, the Constitution of India was finally adopted on November 26, 1949, and came into effect on January 26, 1950, marking the beginning of a new democratic era for India.

7. The Need for a Constitution: Addressing India's Challenges

India’s independence from British colonial rule left behind a deeply fragmented society. The country was marked by social inequalities, a diverse population, and regional disparities. The Constitution was crucial to address these challenges.

- Democracy and Unity: India’s vast diversity made it essential to establish a unified political system. The Constitution created a democratic republic that was based on the ideals of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity.

- Social Justice: The Constitution was a response to the deeply entrenched caste system, gender inequalities, and the exploitation of marginalized communities. It abolished untouchability, guaranteed reservations for Dalits and backward classes, and recognized the right to equality for women.

- Federal Structure: India’s federal structure, with a division of powers between the central government and the states, aimed to balance the country’s vast diversity while ensuring a unified nation.

The historical context behind India’s need for a Constitution is rooted in its long history of diverse governance systems, colonial oppression, and the struggle for self-determination. The adoption of the Indian Constitution marked the fulfillment of centuries-old aspirations for justice, equality, and democracy. It addressed India’s historical challenges while laying the foundation for its future as the world’s largest democracy. Today, as India celebrates 75 years of its Constitution, the document continues to serve as a living testament to the resilience, vision, and hopes of the Indian people.

3. The Constituent Assembly: The Birth of a Republic

The Constituent Assembly of India, convened in 1946, was tasked with the historic responsibility of framing a constitution for the newly independent nation. The assembly's role was not only to adopt a legal document but to shape a vision for an independent, sovereign India that was democratic, secular, and inclusive. The Constitution crafted by the assembly would govern a nation that was deeply diverse, facing monumental challenges in terms of economic development, social justice, and national integration.

1. The Formation of the Constituent Assembly

1.1 Historical Background: From the Demand for Self-Rule to Constituent Assembly

The roots of the Constituent Assembly can be traced back to the demands for self-rule and political autonomy during British colonial rule. India’s struggle for independence, led by movements such as the Indian National Congress (INC) and the Quit India Movement (1942), emphasized the need for a self-determined governance system. Following the Indian Independence Act of 1947, which granted India freedom, the creation of a Constituent Assembly was an inevitable next step.

- The Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946: The British government, led by Prime Minister Clement Attlee, proposed the formation of a Constituent Assembly through the Cabinet Mission Plan. This plan envisaged a body that would frame a new constitution for India, involving the political parties of India in its composition. This assembly was meant to be a representative body, with members elected by the provincial assemblies.

- Selection of Members: The members of the Constituent Assembly were elected indirectly through proportional representation from the provincial legislative assemblies. The INC was the dominant political force, and it won the majority of the seats, though other political entities, such as the Muslim League, Princely States, and Communist Party, were also represented.

1.2 The Composition of the Constituent Assembly

The Constituent Assembly was composed of 389 members initially, with representatives from diverse social, political, and religious backgrounds. The assembly was initially intended to be a body representing all segments of Indian society, though there were challenges to ensure true representation due to the partitions and the political divides of the time.

- The Congress Majority: The Indian National Congress had a clear majority in the assembly, with prominent leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, and Rajendra Prasad leading the charge for drafting a constitution. The INC leadership’s vision for an inclusive democracy shaped much of the discourse during the drafting process.

- Muslim League and Partition: The Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, initially demanded a separate state, leading to the creation of Pakistan in August 1947. The division of the country created a complex situation for the Constituent Assembly, as Muslim representation was reduced significantly after the creation of Pakistan. However, Muslim members like Maulana Azad and Abdul Kalam Azad continued to contribute to the debates.

- Other Minority Groups: There was a conscious effort to ensure representation of various minority groups in the assembly, including Scheduled Castes (now known as Scheduled Castes and Tribes), women, and tribal communities. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a key figure in the drafting of the Constitution, represented the interests of Dalits and marginalized communities.

- Princely States and Regional Representation: The Princely States, which were regions not directly governed by the British but ruled by local kings, were also represented in the assembly.

Following India’s independence, many of these states acceded to India, adding to the complexity of the assembly’s task in framing a unified constitution.

2. The Constitutional Framework: Debating the Vision of India

2.1 The Ideological Foundations: Influences on the Constituent Assembly

The Constituent Assembly was not just a group of elected representatives; it was a forum where India’s future was debated and envisioned. The debates that took place reflected the country’s diverse cultural, social, and political landscape. Several influences shaped the formation of the Constitution:

- Gandhian Thought: Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of a decentralized, self-reliant India was central to the thinking of the Indian National Congress. His emphasis on non-violence, communal harmony, and social justice resonated throughout the process, especially in the drafting of provisions related to Dalit rights and reservations.

- Western Democratic Ideals: The framers of the Indian Constitution were heavily influenced by Western constitutional models, especially the British and American systems. Concepts like fundamental rights, separation of powers, and judicial independence were derived from these democratic traditions.

- Socialist and Marxist Ideals: The socialist faction within the Indian National Congress (including leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose) influenced the Directive Principles of State Policy. They sought a welfare state with provisions for economic redistribution and social equity.

- Indian Traditions: India’s ancient political and legal traditions, such as Dharmashastra, the Arthashastra, and the Mughal administration, were also drawn upon to reflect a governance system that would suit India’s unique cultural context.

2.2 The Committee Structure: Dividing the Work

The Constituent Assembly was divided into several committees, each assigned specific tasks related to different aspects of the Constitution. Key committees included:

- The Drafting Committee: The most important body in the creation of the Constitution, led by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who played a central role in drafting the text. Ambedkar’s work focused on ensuring the protection of the rights of Dalits, minorities, and marginalized communities.

- The Advisory Committee on Fundamental Rights: This committee, headed by Jawaharlal Nehru, was tasked with defining the fundamental rights of Indian citizens. It worked towards creating a vision of equality, justice, and freedom that would be guaranteed by the Constitution.

- The Union Power Committee: This committee, chaired by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, focused on issues of governance and the division of powers between the central government and states. Patel’s strong leadership ensured the creation of a unified federal structure for India.

- The Minorities Committee: Chaired by Sardar Patel, this committee was crucial in addressing the concerns of religious minorities, especially in the context of the violence and divisions that followed the partition of India.

3. Debates and Deliberations: Crafting the Constitution

3.1 The Core Debates

The debates in the Constituent Assembly were intense, as the framers grappled with the challenges of creating a democratic framework that could accommodate India’s diverse languages, religions, and cultures. Some of the most significant debates centered around:

- Federal vs. Unitary System: India’s diversity posed a challenge to the structure of the government. While some members advocated for a federal system of governance that would allow states to retain substantial power, others, led by Sardar Patel, pushed for a strong central government to maintain national unity and integrity.

- The Role of Religion: One of the most complex debates was around the role of religion in the state. While Jawaharlal Nehru and Maulana Azad advocated for a secular state, leaders like Dr.

- B.R. Ambedkar emphasized the need to safeguard the rights of religious minorities. This led to the inclusion of key provisions in the Constitution to protect freedom of religion and promote secularism.

- Language and Cultural Identity: Language was another contentious issue. India is home to hundreds of languages, and the question of which languages should be recognized at the national level was hotly debated. Hindi was eventually declared the official language, but English was retained as an associate language for official purposes to ensure inclusivity.

- Social Justice and Equality: The question of how to ensure equality for marginalized communities was another key area of debate. Dr. Ambedkar, as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee, pushed for provisions that would protect the rights of Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and other backward communities. This led to the affirmative action policies enshrined in the Constitution, such as reservation in education and employment.

3.2 The Final Outcome: A Consensus Emerges

After long and arduous debates, compromises were reached on several key issues, and the Indian Constitution was adopted on November 26, 1949. The debates, though difficult at times, resulted in a document that could unify a deeply fragmented society. It provided a framework that guaranteed fundamental rights, established a parliamentary democracy, and promised a welfare state.

The Constitution came into force on January 26, 1950, and India became a Republic, affirming its status as a democratic nation that would be governed by the rule of law.

4. The Legacy of the Constituent Assembly

4.1 A Document of Vision and Hope

The Indian Constitution remains one of the longest and most detailed constitutions in the world. It is a testament to the vision of the members of the Constituent Assembly, who crafted a document that not only addressed the practical concerns of governance but also reflected the idealistic vision of a just and inclusive society. Its enduring legacy lies in its adaptability and ability to serve as a guiding framework for India’s democratic journey.

4.2 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s Role and Legacy

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar is perhaps the most iconic figure associated with the framing of the Indian Constitution. As the chairman of the Drafting Committee, his vision of social justice, equality, and human rights shaped the Constitution’s provisions. His commitment to abolishing untouchability, empowering marginalized communities, and ensuring equal opportunities for all has made him a symbol of the struggle for justice in India.

The Constituent Assembly's Enduring Vision

The Constituent Assembly was not just a political body; it was a forum for crafting a vision for the future of India. Its debates, decisions, and compromises reflected the diversity, struggles, and aspirations of a newly independent nation. The Constitution that emerged from this assembly laid the foundations for a democratic India, striving for justice, equality, and fraternity, values that continue to guide the country today.

4. The Preamble as a Guiding Vision of the Indian Constitution

The Preamble of the Indian Constitution is a brief introductory statement that sets forth the core values, ideals, and objectives that the Constitution aims to achieve. It is often referred to as the "soul" of the Constitution because it encapsulates the aspirations of the people of India for a democratic, just, and inclusive society.

The Preamble outlines the fundamental principles on which the Constitution is based, expressing the nation's commitment to justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity, all of which are essential to the vision of a fair and equal society. While it doesn't confer enforceable rights, the Preamble is crucial for interpreting the Constitution and guiding judicial decisions.

Preamble is a reflection of national aspirations, its philosophical and historical influences, and the journey through which it was adopted into the Indian Constitution.

1. The Historical Context: Crafting the Preamble

1.1 The Legacy of Indian Nationalism

The Preamble is deeply rooted in the Indian independence movement, particularly the values espoused by leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. The struggle for independence was not just about gaining political freedom from British colonial rule; it was also about creating a nation grounded in democratic principles, human rights, and social justice.

The Indian National Congress played a significant role in shaping the aspirations of the people, particularly through movements like the Non-Cooperation Movement (1920-1922) and the Civil Disobedience Movement (1930-1934). These movements emphasized the principles of equality, freedom, and self-rule, which became foundational ideas in the creation of India's Constitution.

1.2 The Role of the Constituent Assembly

The Constituent Assembly of India (1946-1950) was entrusted with drafting the Constitution after India gained independence in 1947. The Assembly, which comprised prominent leaders from diverse backgrounds, including Gandhians, socialists, lawyers, and revolutionaries, was tasked with creating a document that would embody the aspirations of all Indians.

The framers of the Constitution were deeply aware of the challenges faced by a newly independent nation with immense diversity in terms of languages, religions, cultures, and traditions. In this context, the Preamble was intended to serve as an expression of national unity and an outline of the vision that would guide the functioning of the democratic republic.

1.3 The Language and Tone of the Preamble

The language of the Preamble reflects a sense of hope, optimism, and a commitment to building a just and democratic state. It was written in elevated, dignified language and was inspired by global democratic movements and constitutions, especially those of the United States, France, and Ireland.

While the Preamble is concise, it packs significant ideological weight, blending influences from Indian traditions and global constitutionalism. It articulates not just the philosophy of governance but also the values that would guide the new nation.

2. The Philosophical Foundations of the Preamble

2.1 The Influence of the French Revolution: Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity

The terms Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity are foundational principles in the Indian Preamble and are drawn from the French Revolution (1789), which had a profound impact on the global discourse on democracy and human rights. These values are enshrined as essential tenets of the Constitution.

- Liberty: Represents individual freedoms, particularly the freedom of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship. This is reflected in the Fundamental Rights provided under Part III of the Constitution.

- Equality: The Preamble affirms the commitment to achieving social, economic, and political equality for all citizens, a principle that is reinforced through provisions like reservations and affirmative action policies.

- Fraternity: The ideal of fostering a sense of brotherhood and national unity, transcending divisions based on caste, religion, and ethnicity, is a key objective of the Indian Republic. This is rooted in the idea of social cohesion and mutual respect for the diversity that defines India.

2.2 The Influence of Gandhian Thought

Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence (Ahimsa), truth (Satya), and Sarvodaya (the welfare of all) also influenced the framers of the Constitution. Gandhi's vision of a just society, where the individual’s dignity is upheld and where social and economic justice prevails, was a guiding force in framing the Preamble.

- Dignity of the Individual: The notion of individual dignity is one of the central themes of the Preamble. It aligns with Gandhi's vision of an India where every individual, regardless of caste, gender, or religion, is treated with equal respect and care.

- Nonviolence and Fraternity: Gandhi’s emphasis on fraternity aligns with the Preamble’s call for national unity and integrity, emphasizing social harmony.

2.3 The Influence of Western Democratic Ideals

Western philosophical traditions, particularly those from Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau, also contributed to the philosophical underpinnings of the Preamble. These thinkers emphasized principles such as the separation of powers, the rule of law, and the sovereignty of the people, which were incorporated into the Indian Constitution.

- Sovereignty of the People: The idea that the people of India are the ultimate sovereigns and that the Constitution derives its authority from them is reflected in the Preamble’s opening line: “We, the people of India..”

- Democracy: The Preamble’s affirmation of democratic values echoes the American Revolution and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, which championed the rights of individuals and the principle of self-rule.

2.4 The Indian Context: Unity in Diversity

While global influences played a role, the Preamble also reflects the unique Indian context—a country with immense cultural, religious, and linguistic diversity. The framers of the Constitution sought to create a unified Indian identity that would embrace this diversity without letting it divide the nation.

- Secularism: India’s commitment to secularism is central to the Preamble’s promise of liberty of thought and faith. The secular state was designed to protect religious freedom and ensure that no religion is favored by the state.

- Social Justice: The Preamble underscores a vision of India as a welfare state, dedicated to ensuring social justice for all, especially historically marginalized groups. This aligns with India’s commitment to affirmative action and the inclusion of Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in educational institutions and government employment.

3. The Structure and Content of the Preamble

The Preamble consists of a short and succinct declaration, but it conveys the core aspirations and principles of the Constitution.

3.1 The Key Components of the Preamble

- Sovereign: India is a sovereign nation, meaning it is free to make decisions without any external interference.

- Socialist: The term reflects India's commitment to a society based on social and economic equality. Although the term has evolved, it originally signified a state that would work towards reducing inequality.

- Secular: India does not favor any religion, ensuring equal treatment for all religions.

- Democratic: India is a democracy, where the people elect their leaders and have the power to influence laws and policies.

- Republic: The head of the state is elected, not hereditary, affirming the democratic ethos.

- Justice: Social, economic, and political justice will be ensured for all.

- Liberty: The Constitution guarantees freedom of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship.

- Equality: Ensures equal status and opportunities for all citizens, irrespective of their background.

- Fraternity: Promotes a sense of brotherhood and unity, fostering the dignity of the individual and the integrity of the nation.

3.2 The Significance of Each Term in the Indian Context

Each term in the Preamble is significant in the Indian context:

Sovereign reflects India’s independence from colonial rule.

Socialist embodies India’s goals for economic justice, particularly the eradication of poverty.

Secular highlights the inclusive nature of Indian society, where every religion is equal under the law.

Democratic emphasizes the fundamental principle that sovereignty rests with the people.

Republic underscores that India is not a monarchy but a democracy with an elected head of state.

3.3 The Role of the Preamble in Interpretation

The Preamble is often invoked by the judiciary when interpreting various provisions of the Constitution. While the Preamble itself is not legally enforceable, it provides a framework for understanding the spirit and intent of the Constitution.

4. The Adoption of the Preamble into the Indian Constitution

4.1 The Role of the Constituent Assembly in Framing the Preamble

The Constituent Assembly was tasked with drafting the Constitution, and the Preamble was one of the first elements discussed. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, as the chairman of the Drafting Committee, played a pivotal role in shaping its language and ensuring it reflected the ideals of social justice, democracy, and national unity.

Discussions and Debates: The Preamble went through several revisions in the Constituent Assembly, and it was finally adopted on November 26, 1949. The Assembly carefully crafted the language to ensure it expressed the aspirations of all Indians, regardless of their backgrounds.

4.2 The Evolution of the Preamble

Though the Preamble has remained largely unchanged since its adoption, its interpretation has evolved through landmark judicial decisions. The Supreme Court of India has referred to the

Preamble in numerous cases to uphold the Constitution’s guiding principles, especially in cases related to fundamental rights and social justice.

4.3 The Impact of the Preamble on the Indian Legal System

The Preamble serves as a compass for interpreting the Constitution. The Basic Structure Doctrine, established in the Kesavananda Bharati case (1973), emphasized that the basic structure of the Constitution cannot be altered, a principle grounded in the values articulated in the Preamble.

The Enduring Legacy of the Preamble

The Preamble of the Indian Constitution remains one of the most significant statements of India’s national ethos. It is a reflection of the nation’s aspirations and ideals, guiding India towards the realization of a democratic, inclusive, and just society. Over the years, it has provided a framework for interpreting the Constitution and has helped shape India's constitutional and legal landscape.

The Preamble's influence goes beyond its words, encapsulating the spirit of the Constitution and serving as a beacon for the future of India. As a living document, it continues to inspire and guide the citizens of India in their pursuit of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity.

5. The Pillars of the Indian Constitution: Justice, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity

The Indian Constitution, adopted on January 26, 1950, enshrines a set of ideals that aim to guide the Indian state and its citizens toward building a just, democratic, and inclusive society. At the heart of this framework are four fundamental principles that shape the country’s laws, policies, and social ethos: Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.

These principles are deeply embedded in the Preamble of the Constitution, where it states:

"We, the people of India, having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a Sovereign Socialist Secular Democratic Republic and to secure to all its citizens: Justice, Social, Economic and Political; Liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship; Equality of status and of opportunity; and to promote among them all Fraternity, assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the Nation."

1. Justice: A Social, Economic, and Political Vision

1.1 The Concept of Justice in Indian Philosophy

In India, the concept of justice is deeply rooted in ancient philosophical traditions. Indian philosophers like Kautilya (author of Arthashastra) and Mahabharata explore justice as a central principle. In these texts, dharma (righteousness) forms the core idea, balancing the individual’s rights and duties within the larger societal framework.

- The Role of Dharma: In the ancient Indian context, justice was not merely a legal concept but a moral and ethical principle. The idea of dharma meant adhering to righteous conduct, upholding moral duties, and ensuring harmony within the society.

1.2 Constitutional Justice: A Comprehensive Framework

The Indian Constitution defines justice as a blend of social, economic, and political dimensions. These three facets reflect the commitment to creating a society where all individuals have access to opportunities and are treated with fairness and dignity.

- Social Justice: This aspect of justice ensures that individuals from historically disadvantaged sections of society—like Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs)—are provided the necessary support to uplift themselves. It involves affirmative action, reservation policies, and laws that protect the rights of these groups.

- Economic Justice: The Constitution’s goal of economic justice is reflected in its commitment to reducing economic inequalities and ensuring that all citizens have access to essential services, employment, and resources. Policies aimed at economic redistribution, social welfare, and land reforms are aimed at achieving economic justice.

- Political Justice: This ensures that all citizens have the right to participate in the political process. This is reflected in the universal right to vote, the establishment of democratic institutions, and the guarantee of individual political freedoms.

1.3 Justice in Practice: Judicial Review and Fundamental Rights

The judiciary plays a crucial role in upholding justice. The Supreme Court of India has the power of judicial review, allowing it to strike down laws that violate constitutional principles, particularly those related to justice.

- Judicial Interpretations: Landmark judgments like the Kesavananda Bharati Case (1973) and Maneka Gandhi Case (1978) expanded the scope of justice by interpreting fundamental rights more expansively. These cases illustrate the judicial responsibility in ensuring that justice is not only accessible but also fair and equitable for all citizens.

- Social Justice Laws: Various laws, including those addressing untouchability, child labor, and gender violence, are designed to ensure that social justice is upheld in practice.

2. Liberty: The Freedom to Be

2.1 The Philosophical Underpinnings of Liberty

- Liberty, as a concept, has evolved significantly from the time of John Locke and the French Revolution to modern democratic constitutions. In the Indian context, liberty is not just the absence of restraint but the freedom to develop one’s personality and fulfill one's potential.

- The Role of Liberty in Indian Thought: The idea of liberty in India is linked to the broader quest for self-realization and individual empowerment. From the Bhakti Movement to Gandhian philosophy, liberty was seen as an essential aspect of self-expression and personal dignity.

2.2 Constitutional Liberty: Guarantees of Fundamental Rights

The Indian Constitution guarantees liberty primarily through the Fundamental Rights enshrined in Part III. These include:

- Freedom of Speech and Expression: The Constitution ensures the right to express opinions freely, subject only to reasonable restrictions for maintaining public order, security, and morality.

- Freedom of Assembly and Association: Citizens have the right to gather peacefully and associate with any group or organization, provided it does not disrupt public peace.

- Freedom of Movement and Residence: Every citizen has the right to move freely throughout India and settle in any part of the country.

- Freedom of Religion: The Constitution guarantees religious freedom, allowing individuals to practice, propagate, and worship as per their beliefs.

2.3 The Challenges to Liberty in Modern India

Despite constitutional guarantees, the practice of liberty in India is often challenged by:

- State Repression: Laws such as sedition (Section 124A of the IPC) and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) have often been used to curb dissent and restrict freedom of expression.

- Social Inequality: Caste-based discrimination and gender inequality have often been barriers to the true exercise of liberty for marginalized communities.

2.4 Balancing Liberty and Public Order

While liberty is a cornerstone of the Constitution, it is not absolute. Article 19 permits reasonable restrictions on freedom in the interests of public order, security, morality, and sovereignty. This balance ensures that individual freedoms do not undermine the collective good of the nation.

3. Equality: Equal Status and Opportunity

3.1 The Meaning of Equality in Indian Philosophy

The notion of equality in India is deeply rooted in the traditions of Buddhism, Jainism, and Bhakti Movements, where social hierarchies and caste systems were questioned. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the principal architect of the Constitution, argued for the abolition of the caste system, viewing equality as a key to social reform.

3.2 Equality in the Constitution: Constitutional Guarantees

The Constitution of India mandates equality through various provisions:

- Equality before the Law: Article 14 guarantees that no person shall be discriminated against on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth.

- Abolition of Untouchability: Article 17 prohibits untouchability in any form, ensuring equal treatment for all citizens, particularly those belonging to the Scheduled Castes (SCs).

- Equal Opportunity in Public Employment: Article 16 guarantees that there shall be no discrimination in the employment or appointment to any office under the state on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, or residence.

- Affirmative Action: The Constitution allows for reservations (affirmative action) in educational institutions and public services for SCs, STs, and OBCs to level the playing field and provide them with equal opportunities.

3.3 The Struggle for Equality in Practice

While legal provisions ensure equality, challenges remain in achieving true social and economic equality:

- Economic Disparities: India’s rich-poor divide and unequal access to resources, healthcare, and education continue to perpetuate social and economic inequality.

- Gender Equality: Despite legal safeguards, gender inequality remains pervasive in India. The struggle for gender justice is ongoing, especially concerning issues like rape, dowry, female feticide, and gender-based violence.

- Caste-based Discrimination: Although untouchability has been abolished, caste-based discrimination continues to persist in many parts of India, particularly in rural areas.

4. Fraternity: Ensuring Unity and Dignity

4.1 The Philosophical Roots of Fraternity

The concept of fraternity is linked to the idea of social solidarity and brotherhood. In India, it resonates with Gandhi’s concept of "Sarvodaya" (welfare of all) and the ideals of mutual respect, cooperation, and shared destiny.

4.2 Fraternity in the Constitution

Fraternity is explicitly mentioned in the Preamble, emphasizing the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the nation. The Constitution fosters fraternity by promoting social harmony, reducing divisions based on caste, religion, and ethnicity, and encouraging national integration.

4.3 Promoting National Integration and Social Cohesion

The principle of fraternity is operationalized through:

- Directive Principles of State Policy: The Constitution calls on the state to promote social and economic fraternity by eliminating inequalities and ensuring equal access to resources.

- The Role of Education: The Right to Education (RTE) Act aims to reduce educational disparities, fostering a sense of unity among diverse groups.

- Secularism and Religious Tolerance: The Constitution’s commitment to secularism ensures that no religion is privileged, promoting unity in a multi-religious society.

A Harmonious Balance of Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity

The four key principles of the Indian Constitution—Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity—are not isolated ideals but interwoven concepts that collectively work to build a cohesive, just, and democratic society. They reflect India’s commitment to human dignity, equality, and social justice.

Despite the challenges in fully realizing these principles, the Indian Constitution remains a living document, continually evolving to meet the needs of its citizens and the dynamic social, political, and economic landscape of the country. These principles guide India on its journey to ensure freedom, fairness, opportunity, and social unity for all.

6. Fundamental Rights: Safeguarding Individual Freedoms

The Fundamental Rights enshrined in Part III of the Indian Constitution form a core pillar of India’s democratic framework. These rights are the cornerstone of individual freedoms, guaranteeing protection against arbitrary state actions and ensuring that every citizen can lead a life of dignity, equality, and liberty. The Fundamental Rights not only reflect the aspirations of the Indian people for a just and inclusive society but also act as a safeguard against potential misuse of power by the government.

The Need for Fundamental Rights in India

1.1 Colonial Legacy and the Struggle for Rights

Under British colonial rule, India lacked any substantial constitutional protections for individual freedoms, leaving citizens at the mercy of oppressive colonial laws. The lack of civil liberties was a significant grievance of nationalist leaders. The struggle for independence was, in part, a fight for the recognition of fundamental human rights, particularly the rights to life, freedom, and dignity.

Movements like the Indian National Congress (INC) and leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Subhas Chandra Bose, and Jawaharlal Nehru emphasized the need for social justice, non-violence, and the fundamental rights of individuals. The Salt March and Quit India Movement symbolized the Indian fight against arbitrary rule and exploitation.

1.2 The Role of the Constituent Assembly

With India’s independence in 1947, the Constituent Assembly of India was tasked with drafting the Constitution, with a primary aim of securing basic rights for all citizens. The Assembly's debates were marked by discussions on the need for a constitution that would ensure that the government would not exploit its powers and would recognize the dignity of the individual.

Influenced by global movements like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the Indian framers understood the importance of embedding Fundamental Rights within the Constitution. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the chairman of the Drafting Committee, played a pivotal role in framing these rights, ensuring that they reflected India’s commitment to social justice, equality, and the protection of marginalized communities.

Constitutional Provisions: A Detailed Analysis

2.1 Overview of Fundamental Rights (Articles 12–35)

The Fundamental Rights in the Indian Constitution serve as a safeguard against any arbitrary actions by the government. The provisions of these rights are justiciable, meaning that the judiciary can intervene when they are violated.

These rights are divided into six main categories:

Right to Equality (Articles 14–18)

- Article 14 ensures equality before the law.

- Article 15 prohibits discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth.

- Article 16 guarantees equality of opportunity in public employment.

- Article 17 abolishes untouchability.

- Article 18 abolishes titles and privileges.

Right to Freedom (Articles 19–22)

- Article 19 ensures the right to freedom of speech and expression, assembly, association, movement, residence, and profession, subject to reasonable restrictions.

- Article 20 protects against retrospective punishment and guarantees protection from selfincrimination.

- Article 21 guarantees the right to life and personal liberty.

- Article 22 protects individuals from arbitrary arrest and detention.

Right against Exploitation (Articles 23–24)

- Article 23 prohibits human trafficking and forced labor.

- Article 24 prohibits child labor in factories, mines, or hazardous employment.

Right to Freedom of Religion (Articles 25–28)

- Article 25 ensures freedom of conscience and the right to practice and propagate religion.

- Article 26 allows religious denominations to manage their own affairs.

- Article 27 prohibits state funding for religious institutions.

- Article 28 provides for non-religious education in educational institutions.

Cultural and Educational Rights (Articles 29–30)

- Article 29 allows minorities to conserve their culture, language, and script.

- Article 30 provides minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice.

Right to Constitutional Remedies (Article 32)

Article 32 provides the right to approach the Supreme Court directly for the enforcement of fundamental rights, a mechanism that allows the judiciary to uphold these rights.

Fundamental Rights: Safeguarding Individual Freedoms with Focus on Articles 14, 19, and 21

The Fundamental Rights enshrined in the Indian Constitution are central to the notion of democracy, liberty, and justice in the country. These rights are designed to protect citizens from arbitrary state actions, ensuring that every individual is able to live a life of dignity, free from oppression and discrimination. Among the various rights guaranteed, Articles 14, 19, and 21 hold a particularly significant place in safeguarding individual freedoms. These articles ensure equality before the law, freedom of expression and movement, and the right to life and personal liberty, respectively.

1. Article 14: Right to Equality

1.1 Overview of Article 14

Article 14 of the Indian Constitution guarantees equality before the law and equal protection of the laws. This provision is based on two primary principles:

- Equality before the law: It means that every individual, regardless of their status or position, is subject to the same laws. No person shall be above the law.

- Equal protection of the laws: This implies that the laws must apply equally to all people in similar situations. It mandates that any distinction made between individuals or groups must be reasonable and based on a justifiable ground.

The right to equality is a cornerstone of a democratic society, ensuring that no individual is discriminated against, and everyone is entitled to equal treatment under the law.

1.2 Judicial Interpretations of Article 14

The judiciary has played a crucial role in interpreting Article 14, expanding its scope over the years. While the Constitution guarantees equality, the Supreme Court has clarified that reasonable classification is allowed, but such classifications must meet two conditions:

- Intelligible differentia: There must be a clear and distinct difference between the persons or things that are grouped together and those excluded from the group.

- Rational nexus: The difference must have a rational connection to the object sought to be achieved by the law.

In State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar (1952), the Supreme Court struck down a law that arbitrarily classified cases for trial by a special tribunal, emphasizing that classification must be reasonable and not arbitrary.

1.3 Case Law on Article 14

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978): In this landmark judgment, the Supreme Court held that any law or action violating the principles of reasonableness and fairness would violate the right to equality under Article 14.

- E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu (1974): This case marked an important evolution in the understanding of equality, where the Court held that equality is not merely about treating equals equally but also about ensuring that discriminatory treatment is eliminated. The Court emphasized the need for substantive equality and fairness in the application of laws.

- State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh (2016): This case re-affirmed that Article 14 is a fundamental right and requires strict judicial scrutiny of laws that affect the equality of individuals.

1.4 Impact on Social Justice and Affirmative Action

Article 14 has been instrumental in shaping India’s approach to social justice. While it guarantees equality, it also allows for affirmative action in favor of backward classes, Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and other marginalized groups. Article 15 (prohibition of discrimination) and Article 16 (equality of opportunity in public employment) complement Article 14 in ensuring that policies and laws promote positive discrimination to uplift historically disadvantaged communities.

2. Article 19: Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression

2.1 Overview of Article 19

Article 19 guarantees several freedoms that are essential for individual liberty and the functioning of a democratic society. It includes the following rights:

- Article 19(1)(a): Freedom of speech and expression.

- Article 19(1)(b): Freedom to assemble peacefully and without arms.

- Article 19(1)(c): Freedom to form associations or unions.

- Article 19(1)(d): Freedom to move freely throughout the territory of India.

- Article 19(1)(e): Freedom to reside and settle in any part of India.

- Article 19(1)(g): Freedom to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade, or business.

These rights form the foundation of civil liberties in India, ensuring that individuals can express themselves, associate freely, and participate fully in society.

2.2 Limitations on Article 19 Rights

While Article 19 guarantees several freedoms, these rights are not absolute. The Constitution allows for reasonable restrictions on the exercise of these freedoms under Article 19(2) to 19(6), which includes the following grounds:

- Security of the state

- Public order

- Decency or morality

- Contempt of court

- Defamation

- Incitement to an offense

- Sovereignty and integrity of India

This allows the government to regulate individual freedoms in the interest of national security and public order, among other considerations. However, the restrictions must be reasonable, and any law that imposes these restrictions must pass the test of reasonableness.

2.3 Judicial Interpretations of Article 19

The Supreme Court has consistently interpreted Article 19 to protect essential freedoms, while also balancing the state's need to impose restrictions. Some key judicial pronouncements include:

- Romesh Thapar v. State of Madras (1950): This case established that freedom of speech cannot be restricted except in cases of reasonable restrictions, and such restrictions must be grounded in law.

- Indian Express Newspapers v. Union of India (1985): The Court expanded the scope of freedom of speech to include the right of the press to publish information, thereby reinforcing the democratic principle of free expression.

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978): This judgment extended the scope of freedom of speech by ruling that the right to travel abroad falls under freedom of speech and expression, linking it to personal liberty.

2.4 Role in Protecting Democracy

The freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) is perhaps the most critical aspect of this article. It ensures that individuals can voice their opinions, express dissent, and contribute to public discourse without fear of retribution. This freedom is vital for the functioning of a democratic system, where public participation, debate, and accountability are essential.

3. Article 21: Right to Life and Personal Liberty

3.1 Overview of Article 21

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, and it is often considered the most significant of all Fundamental Rights. The text of Article 21 states:

"No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law."

This provision ensures that individuals cannot be deprived of their life or personal liberty without just and fair legal procedures. It is the most frequently invoked provision in Indian judicial cases, encompassing a wide range of rights beyond the basic right to life.

3.2 Expansion of Article 21: Key Judicial Developments

Over the years, the scope of Article 21 has been significantly expanded through judicial interpretation. The Supreme Court has read into this right a multitude of derivative rights essential for human dignity, such as the right to health, education, and privacy.

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978): In this landmark judgment, the Court held that the procedure established by law must be just, fair, and reasonable, not arbitrary. The ruling expanded the interpretation of Article 21, linking it to the due process of law, akin to the American Constitution’s Fifth Amendment.

- K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017): This case affirmed that the right to privacy is a fundamental right under Article 21. The Court held that the right to privacy is an essential part of the right to life and personal liberty.

- Unni Krishnan, J.P. v. State of Andhra Pradesh (1993): The Supreme Court ruled that right to education is an implicit part of the right to life under Article 21. This decision led to the passage of the Right to Education Act (2009).

- Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan (1997): The Court read into Article 21 the need for laws to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace, marking a significant move toward safeguarding women’s rights and dignity.

3.3 The Right to Life and Dignity

The right to life under Article 21 has evolved beyond mere physical existence to encompass all those aspects of life that make it meaningful and worthwhile. These include the right to dignity, the right to live with health and freedom, and the right to personal security.

3.4 Key Issues in the Application of Article 21

One of the key challenges in the application of Article 21 involves balancing individual rights against state interests in maintaining public order and security. Issues such as preventive detention, capital punishment, and the right to die have been subject to extensive judicial scrutiny under Article 21.

For example, in the Nandini Satpathy v. P.L. Dani (1978) case, the Supreme Court recognized that personal liberty includes the right to be free from arbitrary police detention. Similarly, in the Nirbhaya case (2012), the Court interpreted Article 21 to ensure justice for women who have been victims of violent crimes.

1. Article 32

Article 32 of the Indian Constitution is one of the most significant provisions in Part III, which deals with Fundamental Rights. It guarantees the right to approach the Supreme Court directly for the enforcement of fundamental rights. Known as the "Right to Constitutional Remedies," Article 32 empowers citizens to seek judicial intervention if their fundamental rights are violated, making it a cornerstone of India's constitutional framework. The article plays a vital role in ensuring that individuals can exercise and protect their rights, reinforcing the rule of law and upholding justice in the country.

Text of Article 32

The text of Article 32 reads as follows:

"(1) The right to move the Supreme Court by appropriate proceedings for the enforcement of the rights conferred by this Part is guaranteed. (2) The Supreme Court shall have power to issue directions or orders or writs, including writs in the nature of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto, and certiorari, whichever may be appropriate, for the enforcement of any of the rights conferred by this Part. (3) Without prejudice to the powers conferred on the Supreme Court by clauses (1) and (2), Parliament may by law empower any other court to issue directions, orders or writs in relation to all or any of the matters specified in clause (2). (4) The right to move the Supreme Court shall not be suspended except as otherwise provided for by this Constitution."

2. Significance of Article 32

2.1 The Constitutional Guarantee of Remedies

Article 32 acts as a guarantee for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights. It allows individuals to seek redress directly from the Supreme Court of India when their fundamental rights are infringed upon. The existence of Article 32 ensures that no matter how powerful an institution or authority might be, it cannot violate the basic rights of individuals without facing legal consequences.

In the absence of such a provision, individuals would have to resort to the regular courts, which may be slow or less effective in addressing urgent cases involving violations of fundamental rights. The availability of Article 32 ensures that justice is accessible, prompt, and effective in protecting the rights of individuals.

2.2 Judicial Independence and Role of the Supreme Court

Article 32 strengthens the role of the Supreme Court in safeguarding constitutional rights. It provides the Supreme Court with extensive powers to issue directions, orders, or writs to enforce fundamental rights. The Court’s ability to act as a guardian of the Constitution underlines the importance of judicial independence in a democracy.

The provision reflects the idea that the judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, is not only a forum for resolving disputes but also the primary mechanism for ensuring that citizens’ rights are protected from state encroachments. As the highest court in the land, the Supreme Court serves as the final arbiter on matters related to fundamental rights.

2.3 Access to Justice

Article 32 ensures that access to justice is available even to the poorest or most marginalized citizens. It ensures that individuals can seek justice without having to first exhaust lower courts, making the Supreme Court a direct venue for constitutional remedies. This direct access is crucial for ensuring that constitutional rights are not denied or delayed by procedural barriers.

Furthermore, Article 32 underlines the importance of judicial activism, as the judiciary can step in whenever there is an infringement of fundamental rights, even when the violation is not explicitly covered by the laws.

3. Writ Jurisdiction Under Article 32

Article 32 empowers the Supreme Court to issue a range of writs, orders, or directions for the enforcement of fundamental rights. The Constitution enumerates five types of writs that the Supreme Court can issue under Article 32. These writs are:

3.1 Habeas Corpus

The term "Habeas Corpus" literally means “you shall have the body.” It is issued when a person is unlawfully detained or imprisoned. The writ of habeas corpus is used to seek the release of individuals who are detained in violation of their personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution.

- Example: In the case of A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras (1950), the Supreme Court ruled on the scope of preventive detention laws. Later, in D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal (1997), the Court stressed the use of habeas corpus as a remedy for the violation of rights related to unlawful detention.

3.2 Mandamus

A writ of Mandamus is issued by the court to compel a public authority or official to perform a duty that is mandated by law. The writ can be issued when an authority has failed to perform a legal duty, especially a duty that relates to the enforcement of public rights or duties.

- Example: In State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain (1975), the Supreme Court issued a writ of mandamus directing the state authorities to act in accordance with the law and principles of justice.

3.3 Prohibition

A writ of Prohibition is issued by a higher court to a lower court or tribunal, preventing it from acting beyond its jurisdiction or from hearing a matter that it has no authority over. This writ ensures that no authority exceeds the scope of its powers.

- Example: In the case of Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia v. State of Bihar (1966), the Supreme Court issued a writ of prohibition against the government for taking action without jurisdiction in matters relating to individual freedoms.

3.4 Quo Warranto

A writ of Quo Warranto challenges the legality of a person holding a public office. It is issued when a person is occupying a public office without the legal authority to do so. The writ seeks to ascertain the authority under which a person is holding such an office.

- Example: In K.K. Verma v. Union of India (1954), the Court issued a writ of quo warranto to challenge the appointment of a public official to an office that they were not lawfully entitled to hold.

3.5 Certiorari

The writ of Certiorari is issued to quash or set aside the order or decision of a lower court or tribunal. It is issued when the decision is found to be beyond the jurisdiction or contrary to the law.

- Example: In Shiv Kumar v. State of Haryana (1995), the Court issued certiorari to quash an order passed by the lower courts on the ground of jurisdictional error.

4. Scope and Limitations of Article 32

4.1 Scope of Article 32

Article 32 provides a direct and speedy remedy for individuals whose fundamental rights have been violated. It allows for immediate access to the Supreme Court, which can provide remedies like writs, orders, or directions. This makes Article 32 an essential tool for the protection of rights, enabling citizens to challenge violations of their rights in the highest court without going through the lower courts first.

Furthermore, Article 32 is considered the heart and soul of the Constitution. This is because it preserves the effectiveness of Fundamental Rights, ensuring that there is a mechanism for enforcing these rights. Without the ability to approach the Supreme Court directly, fundamental rights would be merely symbolic and ineffective.

4.2 Limitations of Article 32

While Article 32 guarantees the right to approach the Supreme Court for the enforcement of fundamental rights, there are certain limitations:

- Parliamentary Restrictions: According to Article 32(3), Parliament has the power to empower other courts to issue writs or orders for enforcing fundamental rights. This allows for the decentralization of writ jurisdiction but does not undermine the Supreme Court's role.

- Suspension During Emergencies: Article 32(4) provides that the right to move the Supreme Court can be suspended during a national emergency (as per Article 359). This means that in times of emergency, the right to move the Supreme Court for the enforcement of rights can be restricted.

- Non-Justiciable Rights: Not all rights are justiciable under Article 32. Some directive principles of state policy (Part IV of the Constitution) are not enforceable in court, and hence, cannot be challenged directly under Article 32.

5. Case Laws Under Article 32

Over the years, Article 32 has played an essential role in safeguarding fundamental rights through judicial intervention. Some landmark cases include:

- K.K. Verma v. Union of India (1954): This case dealt with the writ of quo warranto, challenging the appointment of a public official.

- D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal (1997): The Court issued guidelines for the protection of rights during detention, including guidelines for police officers, reinforcing the scope of Article 32 in cases of unlawful detention.

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978): While not directly dealing with Article 32, this case expanded the interpretation of Article 21, and the Court emphasized the effectiveness of Article 32 in ensuring that fundamental rights are not violated.

Article 32 is a foundational provision of the Indian Constitution, serving as the ultimate guarantee for the protection of fundamental rights. It ensures that individuals have an immediate and effective remedy available to them when their fundamental rights are infringed upon. By empowering the Supreme Court to issue writs, the Constitution underscores the importance of judicial intervention in maintaining the rule of law, protecting individual freedoms, and ensuring the rights of citizens.

The continued effectiveness of Article 32 reinforces India's commitment to upholding the principles of justice, equality, and democracy, making it one of the most important provisions in the Constitution. Through judicial activism and strict enforcement, Article 32 has significantly shaped the landscape of human rights protection in India.

Articles 14, 19, 21 and 32 form the cornerstone of Fundamental Rights in India, ensuring equality, freedom, and personal liberty for every citizen. Through judicial interpretation, these articles have evolved to protect not only basic freedoms but also human dignity, privacy, and social justice. However, the ongoing challenge remains to ensure that these rights are upheld for all individuals, especially marginalized groups, and that they continue to serve as the foundation of India’s democratic principles.

The dynamic nature of Fundamental Rights in India ensures that these provisions remain relevant, offering vital protections for individual freedom and dignity in a rapidly changing society.

4. Challenges in the Enforcement of Fundamental Rights (600-700 words)

While Fundamental Rights are crucial to the democratic fabric of India, their effective enforcement faces various challenges:

4.1 Legal and Institutional Challenges

- Slow judicial process and backlog of cases can delay the enforcement of rights, particularly for marginalized groups.

- Judicial access remains limited for many, especially in rural areas, due to high costs and inadequate legal awareness.

4.2 Conflict with State Power

The state often seeks to curtail fundamental rights under the pretext of national security or public order. Laws like sedition and prevention of terrorism have been criticized for infringing on freedom of speech and personal liberty.

4.3 Social Inequality

Despite constitutional safeguards, discrimination on the basis of caste, religion, gender, and economic status still persists. The Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) continue to face social exclusion, and access to fundamental rights remains uneven.

The Continuing Struggle for Rights and Justice

The Fundamental Rights enshrined in the Indian Constitution play a pivotal role in protecting individual freedoms and ensuring justice for all citizens. These rights are not merely provisions in the Constitution; they are a living expression of India’s commitment to democracy, equality, liberty, and social justice.

While there are challenges in ensuring these rights for all, the judiciary has been an active and vigilant protector, expanding the scope of rights through landmark judgments. As India continues to evolve, the Fundamental Rights will remain the backbone of its democratic system, serving as both a shield and a sword for the empowerment of its citizens.

7. Introduction to Directive Principles of State Policy

1.1 Origin and Concept

The concept of Directive Principles of State Policy was borrowed from the Irish Constitution. When drafting the Indian Constitution, the framers took inspiration from several global models, and the Irish Constitution’s inclusion of DPSPs provided a valuable precedent. In fact, the term

“Directive Principles” was specifically borrowed from the Irish Constitution, which itself was influenced by the Constitution of Spain.

The framers of the Indian Constitution envisioned the DPSPs as a set of non-justiciable guidelines meant to steer the government in the right direction toward achieving socio-economic objectives, even though these directives do not confer direct legal rights on the citizens. In contrast to the Fundamental Rights (Part III), which are enforceable by the courts, the DPSPs are not legally enforceable, but they carry immense moral and political weight in the governance of the country.

1.2 The Nature of DPSPs

The Directive Principles are aimed at ensuring a welfare state in India. They lay down the principles that should guide the legislature, executive, and judiciary in the governance of the country. These principles cover a broad spectrum of issues, including:

- Social Justice: Ensuring the welfare of the marginalized and ensuring that the benefits of development reach all segments of society.

- Economic Justice: Promoting policies for the equitable distribution of resources, reduction of poverty, and overall economic growth.Political Justice: Ensuring that citizens have the right to participate in the political process and enjoy political freedoms.

- Cultural and Educational Justice: Safeguarding cultural diversity and promoting education and welfare.

While the Directive Principles are not directly enforceable in a court of law, they are crucial for the functioning of a democratic welfare state. They complement the Fundamental Rights by placing an emphasis on social, economic, and political justice, making the Indian Constitution one of the most comprehensive and visionary documents in the world.

2. Classification of Directive Principles

The DPSPs can be broadly classified into three categories based on their objectives and scope:

2.1 Social and Economic Welfare

These principles are aimed at ensuring the economic and social welfare of the people. They include measures for the improvement of living standards, provision of education, healthcare, and equal opportunities. Key articles include:

- Article 38: Promotes the welfare of the people by securing a social order based on justice.

- Article 39: Directs the State to ensure that its citizens, particularly women and children, are provided with opportunities for adequate livelihood, social security, and equitable distribution of wealth.

- Article 41: Ensures that the State makes provisions for securing the right to work, education, and public assistance in cases of unemployment, old age, sickness, etc.

- Article 43: Ensures the provision of adequate means of livelihood and decent standards of living for all workers, with a focus on improving their economic conditions.

2.2 Political and Administrative Principles

These principles relate to the political structure and functioning of the state, including promoting democracy, participation in governance, and ensuring decentralization of power. They include:

- Article 40: Directs the State to organize village panchayats and empower them to function as units of self-government.

- Article 51: Promotes the international peace and security and calls for the encouragement of respect for international law and relations between nations.

2.3 Cultural and Educational Principles

These principles focus on the preservation of culture and the promotion of education for the betterment of society. They include:

- Article 29: Protects the interests of minorities by ensuring that they can preserve their distinct culture, language, and script.

- Article 30: Grants the right to minorities to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice.

- Article 46: Directs the State to promote the educational and economic interests of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and other weaker sections of society.

3. Relationship Between Directive Principles and Fundamental Rights

The Directive Principles of State Policy and Fundamental Rights are complementary and mutually reinforcing in nature, but they have some important differences:

- Justiciability: Fundamental Rights are enforceable by the courts, whereas the Directive Principles are non-justiciable, meaning they cannot be enforced in a court of law.

- Scope and Purpose: Fundamental Rights primarily protect the individual against arbitrary state actions and ensure personal liberties, while the Directive Principles guide the government in creating laws and policies aimed at achieving social justice, economic equality, and welfare.

- Conflict and Harmonization: At times, there may be a conflict between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles. For example, a law passed to implement a Directive Principle might infringe upon a Fundamental Right. In such cases, courts have tried to harmonize the two by interpreting the provisions in a manner that gives effect to both.

3.1 The Case of Minerva Mills v. Union of India (1980)

In this landmark case, the Supreme Court of India dealt with the conflict between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles. The Court ruled that both are equally important and must be read in a way that allows for their effective implementation. The Court held that Article 39(b) and (c) (which guide equitable distribution of wealth) must be reconciled with Article 14 (right to equality). This case reaffirmed that DPSPs cannot override Fundamental Rights but must be interpreted in harmony with them.

3.2 Judicial Interpretation: Harmonizing DPSPs and Fundamental Rights

The judiciary has played a significant role in interpreting the relationship between DPSPs and Fundamental Rights. The Supreme Court has often emphasized that while the DPSPs cannot be directly enforced in a court of law, they provide a framework for lawmaking that is consistent with social justice and equality.

In Keshavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), the Supreme Court held that while Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution, it cannot amend the basic structure of the Constitution. The basic structure doctrine balances the fundamental rights and directive principles and ensures that neither of them is violated in a way that undermines the foundational principles of the Constitution.

4. The Role of the Directive Principles in Governance

While DPSPs are non-justiciable, they have played a critical role in shaping India's policies and legislation, guiding the development agenda of the government. Here’s how the Directive Principles have influenced governance and policymaking in India:

4.1 Socio-Economic Development

The DPSPs have been instrumental in guiding the government’s efforts to reduce poverty, ensure economic equality, and provide welfare to the marginalized sections of society. The FiveYear Plans initiated by the government after independence were largely based on these principles, aiming to achieve economic growth and social justice.

- Article 38 guided the government in formulating policies aimed at promoting the welfare of citizens, such as land reforms and poverty alleviation programs.

- Article 39 has had a significant impact on policies concerning labor rights, education, and healthcare, ensuring that the government strives for equitable distribution of resources. 4.2 Empowerment of Marginalized Sections

The DPSPs have emphasized the need for social justice and equal opportunities for all sections of society, particularly the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and other backward classes. Laws aimed at the empowerment of women, reservation policies, and initiatives like midday meal schemes and affirmative action are a direct result of the guidance provided by DPSPs.

- Article 46 promotes the welfare of weaker sections, including SCs, STs, and other backward classes, ensuring they receive adequate opportunities for education and economic advancement.

4.3 Environmental and Sustainable Development

While the DPSPs do not explicitly mention environmental protection, several principles in the Constitution have been interpreted by the courts as promoting sustainable development. For example:

- Article 48A (which was added by the 42nd Amendment) mandates the State to protect and improve the environment, including forests and wildlife.

- Article 51A outlines the duty of citizens to protect the environment, highlighting the need for a holistic approach to development.

These principles have influenced key environmental legislations such as the Environment Protection Act (1986) and the Wildlife Protection Act (1972), reflecting the commitment of the Indian state to protect the natural environment.