23 August 2023 – one certain ‘Lander Vikram’ emerged as a household name in India. The country became the fourth overall to land on the lunar surface and the first ever to land on the Moon’s South Pole. For the scientists, engineers, and a large number of workers who worked tirelessly over these years (some, not to forget, with meagre or no salary at all), it was ‘this’ moment they were all waiting for.

The moment, however, is a result of a painstaking journey of research and experiment, which began almost sixty years back.

India launched its first rocket on 21 November 1963 from Thumba, Thiruvananthapuram. Compared to today’s 120-ton SSLV, the US Nike Apache weighed just 715 kg and was taken to the launch site on a bullock cart. So, in a nutshell, India has come a long way.

Now, with the landmark event’s diamond jubilee only a few weeks away, let us go back a bit further from that incident – maybe, five-six years…

It was the late ’50s. The devastating Second World War ended just more than a decade back, with the scar still fiercely visible. However, the world was on the brink of witnessing another nervy combat – this time between the two superpowers. On 4 October 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first ever artificial satellite of planet Earth.

Thus, began a new chapter in global politics: the Space Race.

The story was somewhat different in another part of the world. Calcutta, once a bustling capital of the Raj and the center of 19th-century cultural renaissance, had now turned into a city of crisis. The partition had affected it deeply, with refugees still coming in considerable numbers from East Pakistan and a series of mass upheavals shaping its socio-political atmosphere.

Amid such turbulence, however, the city retained its spirit – the spirit of its own culture and class. Despite struggling to make ends meet, the urban middle class would still gather at a corner of their locality to not only discuss daily matters but also inquire about each other’s wellbeing.

Narayan Gangopadhyay’s evergreen fictional quartet of Tenida-Pyalaram-Habul-Kyabla, whose name has become almost synonymous with the Central Kolkata neighborhood Pataldanga, is the product of this wholehearted community spirit.

Tenida was modeled after the son of the landlord of Narayan who rented their house in the said neighborhood in mid ’40s. The character, known for his big-mouthed attitude, attained a cult status in the Bengali literature spectrum. He is found to dominate (to some extent, exploit) his three younger sidekicks, but at the same time, he loves them with all his heart and can face any danger to save their lives – characteristics typical of these kinds of big brothers found in post-independence and pre-globalization Calcutta.

The first Tenida story was published in 1946, while the first novel came out almost ten years later. ‘Charmurti’ (The Four Heroes) was published serially in the popular children’s monthly, ‘Shishusathi’, over a period of one and a half years (from early ’55 to late ’56) and later as a book from Abhyuday Prakash Mandir in the summer of 1957, only a few months prior to the launch of Sputnik 1.

Tenida stories and novels written around this time clearly reflect the impact of the Race on the Calcutta youth.

Sputnik was first mentioned in a Tenida short story titled ‘The Great Chhantai’ (The Great Haircut), published in a Deb Sahitya Kutir magazine, Aparajita, in mid-1958. In this story, on Tenida’s insistence, Pyala is forced to have a haircut from a roadside barber. But in the end, it is Tenida who wants to cut his hair himself. During his altercation with the barber, he is found to say – “Sob hota. Akashe Sputnik hota – mathame taak hota – murgi aj thyang niye chole berate, kal sei thyang plateme cutlet ho-jata.” (Everything is possible. Sputnik can go to the sky – bald can grow on the head – the chicken that walks with its legs, gets served on a plate as a cutlet the next day.)

The same year, the second Tenida novel ‘Charmurtir Obhijan’ (The Adventure of the Quartet) came out, with the first instalment being published in ‘Shishusathi’ in December 1958.

In this novel, the four are seen flying in a Dakota plane, bound for Dooars. One of Tenida’s maternal uncles, Kutti Mama (‘mama’ means maternal uncle in Bengali) is employed there as a manager of a tea garden. In the small flight, Tenida and Habul are found to get engaged in a verbal fight over the cruising altitude. The former, in his signatory ‘big-brotheresque’ dominance, claims that this plane does not fly at any height below 50000-60000 feet.

The reason behind such a claim? Simple. The plane is from his Kutti Mama’s land.

When Kyabla tries to correct him by saying that Dakota Planes will not fly above 6000-7000 feet, Tenida gets furious. As expected, he is in no mood to accept defeat. Sarcastically, Kyabla goes on to comment that they are flying at a height of one lakh feet, which makes Tenida feel happy and proud.

This conversation eventually leads Habul to comment that they must be so close to the Moon. We can see him requesting Tenida, in his East Bengali dialect – “Ta hoile ektu kou na pilotere. Chander thikya ektu ghuirai jai. Besh berano o hoibo, Russian Sputnik aisa porche ki na sei khobortao nite parum.” (If so, can’t you please request the pilots? A trip to the Moon – it will be a great adventure, you see. We can also find out whether or not the Russian Sputnik had already landed.)

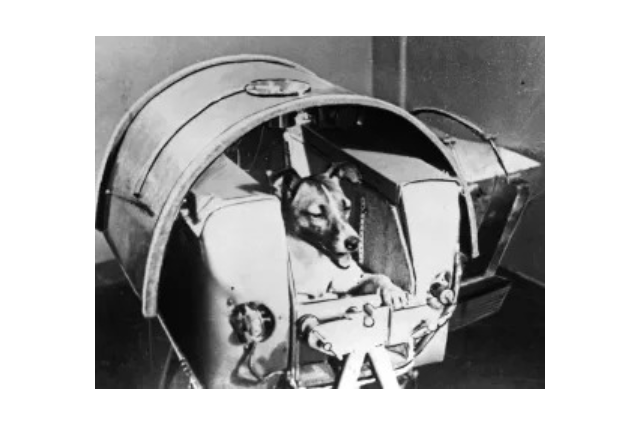

Now, let us have a look at the timeline of the Space Race. The launching of Sputnik 1 was followed by the launching of Sputnik 2 in November 1957, which carried Laika the dog, the first mammal sent into space. While the Sputnik 1 was the first artificial Earth satellite, its younger counterpart was a spacecraft. So, the one Habul is speaking about is the Sputnik 2.

Getting back to the story, Pyala, however, feels confused about the whole conversation. He is the narrator of all Tenida stories, and in his words – “Eto sohojei ki Chande Jawa jay? Kagoje ki sob jeno porechilum. Chand, ki bole – sei koto loksho mile dure – mane, jete-tete anek deri hoy bolei shunechilum.” (Is going to the Moon really that easy? This is not what I read in the newspapers. As far as I know, the Moon is hundreds of thousands of miles away – so, it will take a lot of days, certainly.)

Afraid of Tenida’s beating, he relents himself from expressing his doubts. Soon, he also finds that Habul is actually joking about the whole thing.

Before the discussion takes any unexpected turn, Tenida ends it by uttering, with a big smile – “Accha, next time. Ekhon ektu taratari jete hobe kina – mane Kutti Mama amader jonye etokshon horiner mangser jhol ready kore feleche. Ta chara Russian ar American ra jawar to cheshta korche, oder mone by diye age Chande jawata uchit hobe na. bhari koshto pabe. Amar monta boro komol re – kauke dukkho dite icche kore na.” (Okay, next time. Now, we’re in a little hurry – I mean, Kutti Mama must have already prepared the venison curry for all of us. Apart from that, the Russians and Americans are trying with all their might, so, it will be highly unfair for us to land on the Moon first. My heart is so soft, you know – I cannot hurt anyone.)

The month ‘Charmurtir Obhijan’ started getting published, it was the end of the Third International Geophysical Year (1 July 1957 – 31 December 1958). As promised by the US, they launched their first artificial satellite during this period. The name was Vanguard 1, which was the first solar-powered satellite and launched on 17 March 1958. Nevertheless, their Communist rival certainly had the upper hand in the first phase of the Space Race.

Of the quartet, Kyabla and Habul are shown as academically intelligent, with Kyabla having received a scholarship for his result. On the other hand, Tenida and Pyala are completely dumb in their academics. But, whatever their academic records may be, these words of Tenida indicate that all of them are quite aware of all the preparations related to the Race and the politics surrounding it.

By the time the novel was published as a book, the USSR had already achieved the distinction of ‘touching’ the surface of the Moon. Luna 2, on 13 September 1959, landed on the surface east of Mare Imbrium. Such was the impact of this ‘impact’ event that the Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, during his only visit to the US shortly after, gifted US President Dwight Eisenhower a replica of the Soviet pennants that Luna 2 had placed onto the lunar surface.

A much greater achievement of the USSR would come on 12 April 1961. Major Yuri Gagarin became the first man to space aboard Vostok 1.

However, neither Luna 2 nor Vostok 1 found its place in any of Tenida's novel or story published post-Charmurtir Obhijan. Instead, the Sputniks got mentioned again in the third novel of Tenida, ‘Jhau Bungalow-r Rahosyo’ (The Mystery of the Forest Bungalow), which was published serially in ‘Sandesh’ (a popular 20th century Bengali children’s magazine started by Upendra Kishore Roychowdhury, popularised by Sukumar Ray, and revived by Satyajit Ray and others) in 1962-’63.

This time, Kyabla, while kicking a broom, mocks at the unnecessary fear of a probable bomb blast – “Hoyto or modhye ekta atom bom ache, duto Sputnik ache, barota nengti idur ache? Joto sob roddimarka detective boi pore trader mathai kharap hoye gauche dekhchi.” (Maybe, there is an atom bomb in that broom, or two Sputniks, or twelve house rats, isn’t so? Rubbish! All those trash detective thrillers have made you totally dumb, I suppose!)

So, despite Luna and Vostok’s unprecedented success, the two Sputnik missions did acquire a special place in Tenida’s world.

Now, the use of ‘two Sputniks’ with ‘one atom bomb’ in the dialogue is quite unique, uncanny, and at the same time, noteworthy. Kyabla is being warned by the three to not to touch the suspicious item – a common guideline followed worldwide to avoid IED (improvised explosive device) explosion. So, his mention of rats may be a reference to the idea of rat bombs developed by the British Special Operations Executive to defeat Germany in the Second World War. But, neither an atomic bomb nor Sputnik can be used as an IED. So, doesn’t it sound a bit gibberish?

Well, the explanation lies in the dramatic turn of events post-World War 2. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings by the US not only ended the War but also set the tone for an upcoming Nuclear Arms Race between the Western and Eastern Blocs, while the USSR’s Sputniks gave rise to what we are discussing here. These two conflicts, started by two respective superpowers, on a large part, constituted the Cold War.

So, to conclude, the use of a combination that looks apparently peculiar is actually deliberate, and it only speaks of the creative genius of Narayan Gangopadhyay.

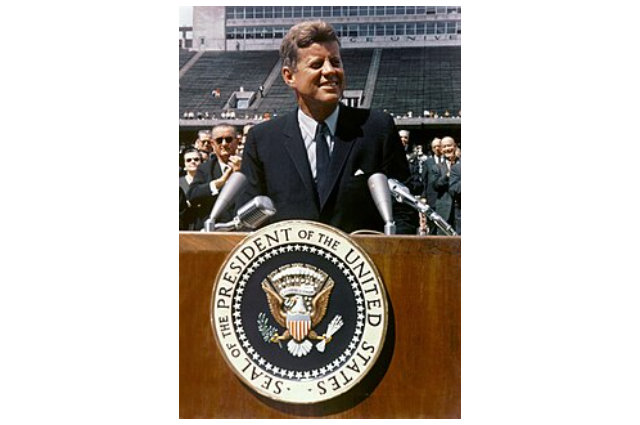

When ‘Jhau Bungalow-r Rahosyo’ was getting published on ‘Sandesh’, another significant incident took place at the Rice University Stadium located in Houston, Texas. On 12 September 1962, the new US President John Fitzgerald Kennedy delivered a speech, now popularly called ‘We choose to go to the Moon’.

In events preceding to the address, the country’s image was tarnished to a great extent. First of all, the USSR’s continued progress led common Americans to start thinking that their great nation was on the verge of defeat in the Space Race. Another major setback was the failed invasion in the Bay of Pigs, Cuba, which took place just five days after Gagarin’s mission. Amid such a precarious scenario, John Kennedy who assumed office in January 1961, recognised that a remarkable achievement was a ‘need of the hour’. It would not only help the US establish its superiority in the Race but also improve its political position on the international front.

In that 18-minute long speech, the President, in his signatory rhetoric, went on to declare: “We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon. We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard…”

Three months after the address, Mariner 2 of NASA completed the first successful planetary flyby mission to Venus (this was also referred to in JFK’s speech).

The youngest ever US President, however, never lived to witness his dream of sending humans to the Moon and bringing them back safely by the end of the decade come true. He was assassinated on 22 November 1963, only a day after the launch of Thumba.

In the same year, Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman-cum-civilian to go to space, flew Vostok 6. She would become a global feminine icon.

Amazingly, Tenida stories or novellas written during this period of 1963-1965 do not contain any reference to either of these incidents.

Then, in mid-1965, came the fourth Tenida novel, ‘Kambol Niruddesh’ (Kambol Is Missing). The story follows the four as they decide to search for Kambol, an orphan and mischievous teenager in their locality who has gone missing. Their urge to find the boy in exchange for nothing is just another example of the indomitable ‘para culture’ spirit once nourished by the Calcuttans.

But, when they go to the press run by his uncle Badri to discuss matters, Badri claims that it will be of no use as Kambol has gone to the Moon. At this point, Kyabla disagrees, in a very similar tone to what Tenida said in ‘Charmurtir Obhijan’ – “Apni eto sure holen kikore, jante pari ki? Je-chande Russianra ekhono obdhi jete parlo na, Americanrao aj porjonto–” (How can you be so sure? The Russians haven’t been able to land on the Moon yet, not even the Americans–”).

Note that both Tenida and Kyabla are putting Russians first, which is nothing but a clear indication of the Soviet supremacy.

Back to the storyline, Badri, as proof, hands them over a piece of paper with a mysterious rhyme written on it. The last line of the rhyme, if translated, look like: “Climb up the Moon – climb up the Moon.” He also claims that his nephew has been highly fond of the Moon since his childhood, and even met with an accident while trying to catch it from the top of a tree.

The rhyme, however, turns out to be a puzzle and leads the four to crack down on a smuggling racket. Unlike most Tenida tales, ‘Kambol Niruddesh’ focuses on crime mysteries and their subsequent investigation where the reference to the Moon plays a major part in solving the mystery.

‘Kambol Niruddesh’ was also published serially first on ‘Sandesh’, from mid-1965 to mid-1966. During this period, two more feathers were added to the Soviet’s crown. On 3 February 1966, the spacecraft Luna 9 managed to achieve a survivable landing on the Moon, thus becoming the first-ever spacecraft to complete a soft landing on another celestial body. It also sent the first photographs of the lunar environment. Then, exactly two months later, Luna 10 became the first artificial satellite to orbit another celestial body, the Moon.

Academically a brilliant student himself (like Kyabla), Narayan Gangopadhyay was a keen observer of the time he lived through. He had taken an active part in the freedom movement of the ’30s, joined the Progressive Writers’ Association in the wake of global fascism, and embraced strong Marxist ideals. He was an avid reader of world literature, history, and politics, and was even interested in linguistics. Thus, while his adult fiction dealt with various crises of wartime, post-war, and post-colonial Bengali society, Tenida and other children’s creations have remained a deep socio-political commentary coated with subtle humor.

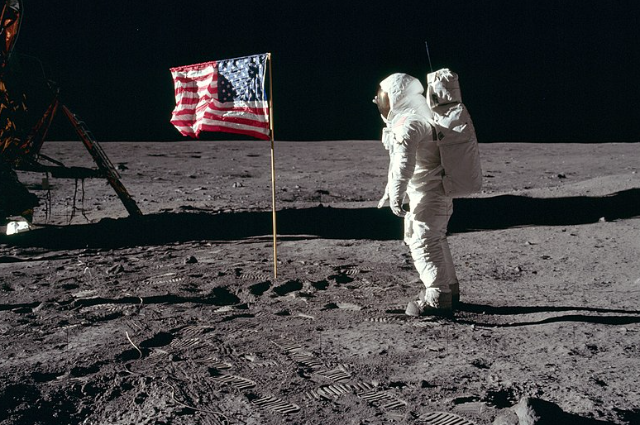

The US ultimately achieved its goal on 20 July 1969. Following the success of Apollo 8 on 21 December 1968, NASA sent Apollo 11 seven months later. The whole world would listen to a voice, pretty loud and clear – “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

There were debates on whether that landing was real or an enactment in a film studio. Even today, YouTubers make money by making entertaining videos on this topic.

But, two things were clear. Firstly, the Moon landing eventually helped the US establish its sought-after supremacy. Secondly, it acted as a clinical ‘distraction from America’s problems’ – the ‘problems’ associated with the ongoing Vietnam War, Civil Rights Movement, etc.

Martin Luther King Jr. was killed just a year back, and the man who held him as he was profusely bleeding, Ralph Abernathy, on the evening of the launch of Apollo 11, led a group of 500 activists to meet one of NASA’s administrators, Thomas Otten Paine. Their protest was against the launch as it represented an inhuman priority amid the intense sufferings of the poor, of whom a majority was black.

Only two Tenida stories were published between the landing and Narayan Gangopadhyay’s untimely death on 6 November 1970. But, surprisingly, following ‘Kambol Niruddesh’, the Race no longer found its place in any of the Tenida tales. The reason might be the emerging political tensions of the period.

‘Prabhat Sangeet’ (The Morning Song) was the only story published in 1969, in the ‘Mahalaya’ issue of ‘Shuko Sari’. While the storyline is filled with humor, as expected, the story itself throws light on another crisis of Modern India – a dormant Hindutva ideal that has persisted among a large section of Bengali urban.

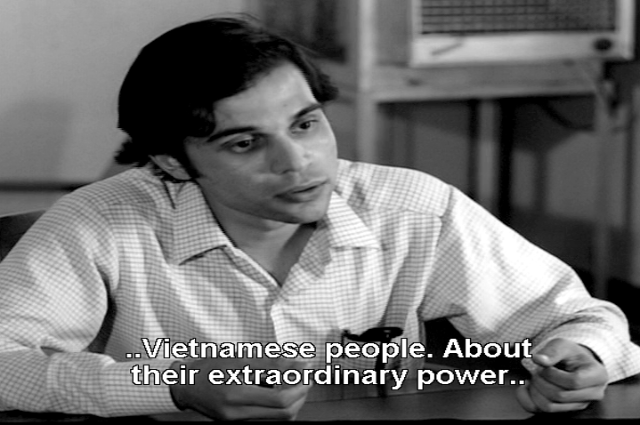

The year Narayan Gangopadhyay breathed his last, Satyajit Ray-directed ‘Pratidwandi’ (The Adversary) was released in theatres. It was that period when hundreds of young men would dress in their best, only to end up standing in long ques for job interviews with little or almost no hope. Such an interview scene from the film would later attain cult status. The board asks the candidate ‘the most outstanding and significant achievement of the last decade’.

The candidate, after a brief pause, answers: “The War in Vietnam, Sir.”

The interviewer, utterly surprised, questions again: “More significant than the landing on the Moon?”

The candidate, Siddhartha Chowdhury, more confident this time, answers promptly: “I think so, Sir.”

Can’t we call it a generational shift – a shift from Tenida’s derisive mockery of the Race to Siddhartha’s much louder rejection of it?

References:

- “1963: First Rocket Launched from Thumba.” Frontline, 22 August 2022.

- Space race – Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

- Narayan Gangopadhyay. Tenida Samagra, Ananda Publishers Private Limited, 1st Edition, pub. 1996.

- Tenida Treasury Blog

- Bay of Pigs Invasion – Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

- We choose to go to the Moon – Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

- Explosive rat – Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

- Nuclear arms race – Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

- Kathleen Alcott. “The Apollo 11 moon landing was a distraction from America’s problems.” The Guardian, 19 July 2019.

- ‘Pratidwandi’, directed by Satyajit Ray