A prelude to start with…

It was 12th November 2022. The Delhi Police had arrested certain Aftab Ameen Poonawala on the basis of a complaint filed by one Mr. Vikas Madan Walkar of Mumbai who had arrived in Delhi just four days back in search of his missing daughter, Shraddha Walkar.

What followed in the next few days was the unfolding of one of the most gruesome murder cases in the country’s history.

During the interrogation, Aftab confessed how he killed his live-in partner Shraddha, chopped her lifeless body into thirty five pieces, and dumped those in several locations around Delhi. The killing took place on 18th May that year, and the dumping was carried out by the accused himself over the next two and a half weeks. Aftab used to leave his apartment building at 2 AM every day and would go into the forest on the outskirts to throw the body parts of someone he loved and lived together for several years. He even took the help of internet to learn the methods of removing evidence by using chemicals.

Such cold-blooded brutality of the incident came as a shock to not only the people associated with the case but also a large section of the Indian community. But, the more shocking aspect was that, as police sources told the media, Aftab felt no sense of remorse during his confession.

Another incident occurred just a few days before Shraddha’s murder in Baharampur, Murshidabad of West Bengal where a graduate student, Sutapa Chowdhury was stabbed to death by her ex-lover on the street beside the mess she used to stay in. The accused, Susanta Chowdhury, arrested the day after, claimed in his interrogation that he loved Sutapa so much that it was hard for him to accept the break-up, and this rejection eventually triggered him to take such a horrific step.

Nevertheless, just like Aftab, Susanta was also told to not have any regret for what he had done. He even asked the police for confirmation about Sutapa’s death.

These two tragic incidents have been highly publicised in media. Public reactions included victim blaming, too. One union minister even put all the blame on live-in relationships behind rising crimes.6 Needless to say, these types of comments only shift the focus away from the root problem.

However, considering the overwhelming number of women falling victim to domestic violence in India each year, Sutapa and Shraddha constitute only a tip of the iceberg. The increase in domestic violence cases by 53% over a period of 18 years, as revealed in a 2022 analysis only adds to this.

Well, I don’t wish to talk much about these statistics or draw an emphasis here, though they form a significant background of my essay. Rather, my objective here is to revisit another similar incident that happened in the late nineteenth century Bengal.

The incident

The year was 1873.

The Bengal Sati Regulation entered into its 44th year, while the Widow Remarriage Act into its 17th.

15 years completed since the transfer of power to the British Crown.

The memor;y of assassination of Lord Mayo (Richard Southwell Bourke, 6th Earl of Mayo) by Sher Ali Afridi in the convict settlement of Andaman Island, which was the first and only incident of assassinating a Viceroy in British India, was still fresh.

The Act III of 1872 (the first ever civil marriage law of India) had recently been introduced, courtesy Sir Henry James Summer Maine.

Bengali public theatre had just been revived with the formation of National Theatre in north Calcutta who staged their first play ‘Nil Darpan’, a classic political text by Dinabandhu Mitra on 7th December 1872.

Michael Madhusudan Dutta, one of the greatest iconoclasts of Bengali literature, passed away on 29th June 1873 but his dream of letting female actresses act on stage came true when Bengal Theatre (another north Calcutta-based professional theatre company run by Sarat Chandra Ghosh and Bihari Lal Chattopadhyay) staged his play ‘Sharmistha’ on 16th August 1873, and used two of the four women they hired from the red-light area of Sonagachi – Jagattarini, Elokeshi, Shyamasundari, and Golapsundari.

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, the father figure of women education in Bengal left Calcutta for Karmantar, a Santhal village in the Santhal Parganas (now in Jharkhand, then a part of Bengal Presidency).

Queen Victoria was just 3 years away from being titled ‘Empress of India’.

British India was yet to get its first female graduate, which eventually materialised 10 years later.

An entity like Indian National Congress was still a day dream.

And, Calcutta, the charismatic capital of British India and the second most important city of the entire Empire, continued to be “the Queen Bee’s chamber in the honey comb of the Empire, which attracted people from far and wide.”

Among these people was certain Nobin Chandra Bandyopadhyay from Hooghly district. Nobin at that time, was working at a printing press in Calcutta. It was a government job, and thus provided the village man with the necessary security – financial and social.

As per social norms, Nobin Chandra was a ‘Kulin Brahmin’ who was married to a beautiful, young girl from a Brahmin family, . Their marriage happened six years earlier when the bride was only ten. Because she hadn’t reached the age of puberty and her husband was away, Elokeshi used to stay at her father’s home.

As time passed, signs of puberty started appearing on her tender body, and she became quite attractive to others’ eyes. Nobin loved his beautiful wife, and was now asking for a child (a son obviously, who would become his ‘heir’), to which Elokeshi happily agreed.

Everything was going fine until one day when Nobin heard of something unexpected. It was all about the ‘illicit’ love affair between his wife and Madhav Chandra Giri, the head priest (Mahant) of the popular Taraknath Temple of Tarakeswar, around 7 kilometres from Kumrul.

When and how Elokeshi fell into the trap of Madhav Giri had several explanations. The most circulated one was that it was actually a plan orchestrated by Mandakini Mukhopadhyay, her step-mother who was much younger than her husband. It was said that Mandakini took Elokeshi to Madhav Giri for seeking childbirth medicine, and Mahant had fallen for the teenage girl. Her father was poor, and thus not capable of fulfilling desires of his young wife. So, he was left with no option but to agreeing to Mandakini’s plan of sending their daughter to Mahant. Some sources also told about the involvement of certain women neighbor (Teli Bou who also received bribes from the Mahant and would flee later).

Whatever the backstory might be, the news devastated Nobin who loved his wife so much. He returned to Kumrul on 24th May and heard gossips about it, which only made the situation worse. He quarrelled with his father-in law and confronted his wife to know the truth. As was written in newspaper reports and depicted in artworks and plays, Elokeshi’s innocent confession satisfied Nobin, and he even arranged transport to take her to Calcutta.

But, Madhav Giri’s goons were all around the village. They kept close watch on every move of the young government servant so that nothing would go as he planned.

As a result, three days after his return, Nobin, the ‘loving and forgiving’ husband who felt utterly betrayed by the whole course of action did something that would remain a talk of the town for years to come. He picked up an anshboti (a steel blade fixed to a wooden base used for cutting fish; ‘ansh’ means ‘scales of a fish’) and decapitated his sixteen-year old sweetheart, his love of life, his wife, Elokeshi.

The entire incident was colloquially termed ‘The Tarakeswar Affair of 1873’.

The events that followed…

The death of Elokeshi could have been just another death of a helpless teenage wife. Statistical reports revealed that of the total murders committed in the period of 1870-1875, 20-40% were of killing of wives believed to be engaged in extra-marital affairs. Elokeshi’s memories could have easily been lost in that 20-40 percent.

But it didn’t.

The involvement of a head priest not only helped the affair get more attention but also mobilised a large group of people against religious dominance. They would travel together to attend court sessions in Serampore (actually Srirampore, the very city where William Carey, along with William Ward and Joshua Marshman, established the famed Baptist Mission Press in 1800 because of East India Company’s hostile attitude towards the missionaries and the protection assured by the city’s Danish administration).

As depicted in plays and also reported in newspapers, immediately after the beheading, Nobin surrendered himself to the local police.

In an anonymously written and published play, ‘Aajkar Bajar Bhau’, the character based on Nobin, also named Nobin (Nobin Madhab Bandyopadhyay) is found wailing in front of the police: “Uh hay! Aamar priya kotha gelo (darogar proti) koi rawkter daag, ami ki khun korechi? Aamake ki fansi debe? To dao hah hah hah hah (uchcheswore hasyo).” (The translation will look like: “Alas! Where has my sweetheart gone (addressed to the Inspector) there’s blood all around, oh, did I kill her? Will you people hang me? Then do it, please. Hah, hah, hah, hah (laughter in loud).”)

However, Madhav Giri had no intention to go quietly into the night. He fled to French-ruled Chandernagore (present day Chandannagar) where adultery was not a crime. The British police force had to take help from Joy Krishna Mukhopadhyay, the influential jamindar of Uttarpara to capture him.

A criminal case was brought against Nobin where the authorities framed him with murder charges. Subsequently, Nobin brought charges of adultery against Madhav Giri. The whole case was entitled ‘Queen Vs. Nobin Chandra Banerji’.

The public sympathy was with the husband, off course. From educated elites to less privileged ones, everyone demanded his release without clause. Mahant was the one who was blamed the most. Portrayal of Elokeshi, however, was mixed. While some plays and farces portrayed her as an innocent victim drugged and raped by a powerful religious chief, some portrayed her as a seductress, and thus a root cause for her own death at the hands of her husband.

Court sessions used to be attended by so many enthusiasts that the authority had to introduce entrance tickets for controlling public. In that sense, it was pretty correct that the reformist newspaper Bengalee compared these gatherings to the audiences who “would flock to the Lewis Theatre to watch Othello being performed.”

Lewis Theatre was established in 1871 (some said, 1873) by George Benjamim William Lewis at Chowringhee Road. He opened another theatre back in 1967, known as Lyceum Theatre, and earned huge fame for his stage productions, which included Shakespearean and other English plays. According to sources, their productions were of highest quality. Lyceum Theatre was situated near the Ochterlony Monument (today’s Shahid Minar) in Calcutta’s Maidan area. George Lewis, along with Rose Edouin Lewis (nee Bryer), his wife and lead actress of his company left Calcutta in 1870 for Melbourne. They returned to this city one year later and founded Lewis Theatre, which became Royal Lewis Theatre in 1875 when Prince of Wales visited it.

Coming back to the main topic, Nobin was defended by W. C. Bonnerjee (Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee), who would become the first president of Indian National Congress twelve years later. Bonnerjee’s skills and ability to defend his client proved initially pivotal because The Indian jury at the Hooghly Sessions Court acquitted Nobin of his guilt on the grounds of insanity. However, the British judge Charles Dickenson Field overruled it and passed the case to the Calcutta High Court. The High Court judges, A. G. Macpherson and G. G. Morris, despite admitting that adultery had happened, found Nobin ‘sane and guilty of culpable homicide’ and sentenced him to transportation for life under the section 302.

On the other hand, Mahant Madhav Giri was also defended by two well-known British judges, W. Jackson and Griffith Humphrey Pugh Evans. Hooghly Session Court sentenced him 3-year rigorous imprisonment and a fine of two thousand rupees, against which he appealed to the High Court. In Calcutta, his case was taken care of by justices William Markby and E. G. Birch, both of whom found him guilty under the newly added Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code 1860.

Amazingly, while Mahant served his full term, Nobin was released in 1876 on clemency grounds on the occasion of the grand India tour by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (Queen Victoria’s eldest son who would later become King Edward VII).

“Public pressure,” opined the press.

The long-term influence on art and market

One of the most valuable aspects of the Tarakeswar Affair of 1873 was the deep impact it left on the contemporary art and indigenous market.

I have already mentioned plays composed around this topic. As Sripantha noted in his book ‘Mohanto-Elokeshi Sambad’, in between 1873 and 1876, nearly three dozen plays and farces were published. While most of these plays were sold at a cheaper rate of 1 anna and 6 paisa, some illustrated productions were also available at higher rates. Among these illustrated ones, ‘Aajkar Bajar Bhau’ contained the highest number of drawings (8). Others included ‘Mohanter Chakrabhraman’ by Bholanath Mukhopadhyay (4 illustrations), ‘Madhav Giri Mahanta Elokeshi Panchali’ by Mahesh Chandra Das De (3 illustrations), and ‘Uh Mohanter Ei Kaaj!’ by Jogendra Nath Ghosh (4 illustrations).

Another play worth mentioning here is ‘Mohanter Ei Ki Kaaj’ (not to be confused with ‘Uh Mohanter Ei Kaaj!’) by Laxmi Narayan Das. Though ‘Sharmistha’ did create a stir by fielding female stage actors on a regular basis, it failed to attract mass attention. Bengal Theatre was about to be closed down. Suddenly, Das’s play came out and out of nowhere, it proved a jackpot for them. One of the managers, Bihari Lal Chattopadhyay himself played the role of Mahant. The craze was so intense that every night, hundreds of people would return empty-handed. This incident was narrated by ‘Rasaraj’ Amrita Lal Basu in his memoir, himself a renowned playwright and actor of his time.

Apart from these plays and farces, Mahant-Elokeshi affair found its place in other literary forms, too. For example, ‘Debgoner Mortye Agomon’, a satirical text published much later had a mention of it. The author, Durga Charan Roy had written the whole book in the form of a conversation. In the satire, Gods of Hindu mythology had come to visit the earthly world and were taking a trip around Bengal. Varun, the Rain God was assigned the task of narrating the key incidents of nineteenth century to Brahma, the God of Universe.

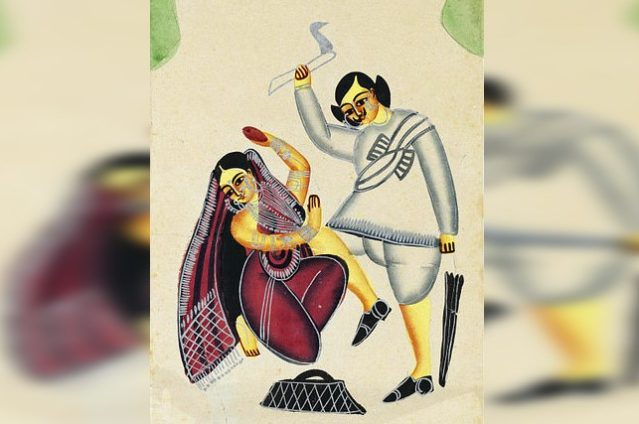

Kalighat pot paintings constitute a significant part of nineteenth century Indian art. As the name suggests, it developed in Calcutta’s Kalighat area, a ‘Shakti Peetha’ situated on the banks of Adi Ganga. According to the classification made by William George Archer and Mildred Archer, there were four distinct phases of Kalighat paintings. Tarakeswar affair happened during its third phase (1870-1885).

Because these paintings were bought by pilgrims coming to Kalighat, in the first two phases, the central focus was mostly Hindu gods and goddesses. But as time passed, the artists were gradually shifting their focuses to elements of everyday lives including English rulers, Bengali elite ‘babus’, women in different moods, scenes from contemporary novels, and off course, social issues. Tarakeswar scandal did find a special place in the artists’ imagination.

A series of paintings was produced, each depicting separate events associated with the scandal. Use of colours and intricate detailing of the figures are two noteworthy features of these paintings. In fact, Hana Knizkova, the art historian from Prague who identified 35 drawings in this series, noted that the period around 1870 was “the summit period of development, representing the highest artistic level of all surviving drawings of the Kalighat style.” (The Drawings of Kalighat Style, 1975)

Raja Mitra, a reputed Bengali filmmaker from Kolkata, had made a national award-winning documentary entitled ‘Kalighat Paintings and Drawings’ in the early 2000s. For his film, he used a 2-minute dramatised version of the incident where Sikta Biswas played the role of Elokeshi, while Alik Das that of Madhav Giri. This is perhaps the only film adaptation of Tarakeswar Affair till date.

Mitra’s take on this treatment and the overall incident was – “I used professional actors to recreate the scene because of only one reason: freshness. Audiences would have got bored by continuous voiceover and still images. And, talking about Madhav Giri, I would say he was nothing compared to today’s corrupt religious chiefs.”

Like those farces, Kalighat pots also attracted a large number of people, regardless of their class. Sripantha mentioned in his book: “Mohanto aar Elokeshir pot enke kuliye uthte parchhen na Kalighater potoparar chitrokorera.” (Translation: “The artisan community of Kalighat just couldn’t keep the pace with the rising demand for Mahant-Elokeshi pots.”)

Another localised art form that drew its inspiration from the incident was the woodcut prints of Battala area near Chitpur, north Calcutta. Compared to Kalighat pat paintings, the number of artworks produced may be less, but they are no less important.

Ashit Paul, a prominent Kolkata-based painter, sculptor and art historian had intensely researched on these Battala artworks. His critically acclaimed book ‘Woodcut Prints of Nineteenth Century Calcutta’, published in 1983, has been a fundamental text for the woodcut enthusiasts over the last four decades. When I personally asked him about the influence of Tarakeswar scandal on the Battala artists, he replied:

“The main reason behind Tarakeswar Affair getting much attention was the extensive coverage by print media. Media coverage was also the factor that played a crucial role in motivating artists to produce their artworks. When Kalighat painters produced a series of paintings, much like a modern-day film, Battala artists decided to do the same. They refused to fall back. In addition to single paintings, some of the plays and farces were also published on woodcuts. Actually, Battala had always had a voice of anti-establishment at its core. Be it their woodcuts or literature, you will always find how they made a mockery of not only these kinds of corrupt religious chiefs but also state tyranny.”

Several country songs were also composed. Let me mention here two such songs: “Ginnir Tarakeswar jawa hobe na, korta korechhe mana” (Translation: “She cannot go to Tarakeswar because her husband forbade her to do so.”) and “Bolire deke deke, dekhe sikhe le re tora. / Pordar papachare Mohanter ghani ghora. / Chhilo se rajbhoge, molo ki chhai rajroge. / Jemon rog temoni tahar ghani gachhe oshudh pora.” (Translation: “I’m calling you people, come, look, and learn. / Look how Mahant is paying for his sins. / He was enjoying royal luxuries, and it’s his royal vice that destroyed him. / As is his vice, so is his labour in the prison.”)

Most of these songs were sung in panchali tune, and thus gained immense popularity among household women.

However, this was not all. Sale of delicate commodities like hookahs, metal-made betel-leaf trays, sarees, and fish-cutting bontis was hugely impacted as well. Manufacturers started engraving Mahant and Elokeshi’s names on their products, which spiked their sale overnight. An ointment believed to be prepared using the oil the Mahant had manufactured as a part of his prison labour also became hugely popular.

And, this was how Elokeshi, at the cost of her own life, changed the fortune of many.

A critique

Before going deeper into it, I would like to mention another incident involving a Tarakeswar priest that happened nearly half a century before this ‘celebrated’ one.

In March 1824, Srimanta Giri, the then Mahant was arrested by the local police for murdering certain Ram Sundar. The victim was a resident of the nearby Jagannathpur village, and was believed to be the lover of the Mahant’s mistress. Srimanta Giri was subsequently hanged on 27th August.

So, Madhav Giri was not the first head priest from Tarakeswar to be put under trial.

Also, around the time the case first exploded, similar charges were brought against the Mahants of Sitakund and Chandranath in Chittagong of erstwhile East Bengal (now, Bangladesh). Another Mahant was killed by local peasants because of oppression of tenants and misconduct in Begusarai in Monghyr (now, Munger of Bihar) in the same year.

But, in the end, it was the Mahant-Elokeshi Affair that stole the limelight.

Why?

Well, I had already mentioned two most obvious factors. Number one, extensive media coverage. Number two, involvement of a religious chief. Note that despite newspapers did play a crucial role, it was still an external factor. Whereas, the second reason was all about the case’s internal character.

For instance, unlike Kalighat and Battala artists, most people who wrote plays and farces did not have any experience of writing plays at all. They only did so to expose the ‘real character’ of a priest, thus acting as reformists. Sripantha, in his well-researched book ‘Mohanto-Elokeshi Sambad’, had spoken of a certain playwright who visited Mahant in his prison cell and informed, “I’m writing a play on you, and have plans to self-publish it. It will be staged very soon so that everyone will start hating you.”

Therefore, talking about the scandal’s internal character, exposing a Mahant had become a principal objective. But, it was not the only one. William Archer, from an artist’s point of view, identified two more. After studying the Kalighat series, he concluded that the artists saw the scandal and its subsequent trial as a triumph of traditional Hindu values and some of them visualised Elokeshi as the Goddess Kali who literally destroyed her ‘illicit’ lover and her ‘legitimate’ husband.

Because Archer’s latter opinion conforms to a niche of painters, let us concentrate on the former one, which has a more universal tone.

What happened in court indeed validates his observation regarding the conventional Hindu customs. Woomesh Chunder did everything possible to prove that Nobin was innocent. Because no one was present at the time Nobin decapitated his wife and yet three family members (Anandamoyee, Nil Kamal, and Muktokeshi, Elokeshi’s younger sister) testified against him, Bonnerjee claimed that all the witnesses lied. He even reminded the jury that because infidelity was worse than death, Nobin’s crime was much less compared to the other two involved. Nobin himself did not hesitate to confess that he was the one who murdered his own wife (although he was reported to change his stand completely during the trial), but Bonnerjee argued that this confession was actually ‘made under severe emotional stress’.

Archer’s observation can be further supported by the fact that the people outside the court who were shocked by Field overruling the jury’s decision, rejoiced after hearing Mahant’s sentence. Mahant’s punishment was also seen as a victory of poor over rich.

Hindu Bengali ‘babus’, on the other hand, was more concerned about the ‘infidelity’ of a Hindu women rather than Mahant’s punishment.

Keeping numerous wives and mistresses, spending thousands to lakhs on unnecessary ceremonies like pujas, cat weddings, etc. were some of the famous (or, infamous) activities carried out by these ‘kulin Brahmins’ of nineteenth century Calcutta. Smaller cities were no exception, either. ‘Ramtanu Lahiri O Totkalin Bongosomaj’ by Shibnath Shastri, one of the great scholars and social reformers is a fundamental documentation of this period. While talking about Jessore (now, in Bangladesh), he mentioned: “Rokshita streeloker paka bari koriya dewa ekta mansombhromer karon chhilo.” (Translation: “Constructing a mansion for a mistress was a matter of prestige (for the babus).”)

Other contemporary texts like ‘Hutom Penchar Noksha’ by Kali Prasanna Singha, ‘Aponar Mukh Apuni Dekho’ by Bholanath Sharma, ‘Dutibilas’ by Bhabani Charan Bandyopadhyay documented how these babus would go for a pilgrimage. From horse-driven carts to women, there was no limit to their luxuries.

Fascinatingly, these people started shouting: “Elokeshi was an unchaste wife.”

Some of the plays echoed the same sentiment. They portrayed Elokeshi as a seductress and Mandakini as the main culprit. Moreover, the teenage wife’s stay at her parents’ house and not at in-laws’ was identified as the direct cause for Elokeshi’s death.

One playwright showed that Madhav Giri was actually the human incarnation of Nandan, grandson of Kubera, the God of Wealth and Elokeshi was his real wife in heaven. Nandan was cursed and was born as Madhav, whose ‘harassment’ at the hands of authority angered Goddess Durga. The playwright went a step further and put the blame entirely on Nil Kamal and Mandakini who were found to be thrown into hell after their mortal death. Elokeshi was also sent to serve one year among female spirits.

It is a fact that for a married woman, staying at her parents’ home for a longer period has never been taken easily by the patriarchal society, and it happens still today.

What happened to Elokeshi was completely unexpected, and thus it was easy for conservative society to blame the poor Mukhopadhyay family at a larger extent. While discussing ‘Uh! Mohanter Ei Kaj’, Tanika Sarkar noted, “Sympathetic older relatives advised her that fidelity to her husband was a more urgent and superior need than obedience to her parents, that the married woman has no master other than her husband.”

Mandakini might have an instrumental role in sending her step-daughter to a wealthy womaniser like Madhav Giri, and Nil Kamal might also have given his consent. But, before putting all the responsibilities on them, we have to understand one simple thing: social hierarchy. Madhav Giri had all privileges necessary to pose as a headman of the society. He had money, he had influence, he had paid goons, and above all, he had his ‘religious shield’. On the other hand, Nil Kamal was only a poor Brahmin who had a young wife and two daughters at his house – one married, and one married-to-be. So, it can be imagined how difficult it could be for a poor housewife like Mandakini to reject Mahant’s offers.

Interestingly, both Mandakini and Nil Kamal died within very short span (Mandakini on 8th September, just before the second hearing at Hooghly Session Court, and Nil Kamal before Mahant’s trial at Calcutta High Court).

Death of two witnesses during a trial – was there no reason at all?

Unfortunately, no investigation was carried out. Two other people who were alleged to be part of this conspiracy, Teli Bou and Kenaram, Mahant’s acquaintance, fled from Kumrul just after the murder. No attempt was made to catch them, either.

But what was more interesting was that Nobin was never blamed for what he had done. Even if we consider his other sides, including his love for Elokeshi and his honest confession to the authority, at the end of the day, he was a murderer. In whatever mental state he was in at that moment, he took life of another person who was helpless and innocent. Yet, Bengali society, as a whole hailed him as a hero who did a great job by killing his wife rather than rejecting her.

For men and women, he became an ‘icon of true masculinity’.

Swati Chattopadhyay writes: “The violence of Elokeshi’s death was not simply justified in the public eye that found sympathy with Nabin, but even for those who found sympathy with Elokeshi, her death was naturalized as a price for transgression, even if she might not have been “at fault.””

Nobin was mad and vengeful, and his anger ignited more when his plan to take Elokeshi with him to Calcutta was ruined by Madhav Giri’s men. Then suddenly, he hit his wife thrice with a sharp object. So, can’t it be concluded that Nobin was well aware of his social status and influence compared to Mahant and the fact that Elokeshi was a much softer and easier target to hit?

Tragically, there was no one present that day to raise this argument.

Concluding note…

Nobin Chandra Bandyopadhyay returned from Andaman in 1876, courtesy royal mercy granted by Prince Edward. After his return, he was reported to visit the office of ‘Hindoo Patriot’ (a native-run English newspaper based in south Calcutta, which reached its peak during the editorship of Harish Chandra Mukherjee) where he expressed his gratitude to Viceroy Lord Lytton (Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton) and Sir Richard Temple, Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal. About the convict settlement of Port Blair, his opinion was that all convicts lived there like a family.

Mahant Madhav Giri returned, too. And guess what, he was back to his form. Not only did he remove the incumbent Mahant Shyam Giri from his post but also started adultery again. Two popular Bengali journals, ‘Bongodorshon’ (edited by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay) and ‘Sanjibani’ (edited by Krishna Kumar Mitra) hugely protested against his activities, with no effect at all.

But no one cared what exactly happened to Elokeshi’s grandmother Anandamoyee or her sister Muktakeshi.

Only silver lining was that Elokeshi’s death did not go completely in vain. In 1924, exactly hundred years after the execution of Srimanta Giri, a non-violent mass movement was organised against the century-long misconduct by Mahants of Tarakeswar. Prominent Congress leaders ‘Deshbandhu’ Chittaranjan Das and Subhas Chandra Bose took the leadership in their hands, thus helping the movement gain strength. In the end, Mahant Satish Giri was removed from his post and his disciple, Prabhat Giri was appointed the new Mahant. All the power was now transferred to a newly formed committee. During this ‘Tarakeswar Satyagraha’, Elokeshi’s death was reported to be mentioned frequently.

Or, may be, Elokeshi hadn’t died.

Even after one hundred and fifty years, when incidents like Jyoti Singh, Asifa Bano, Shraddha, or Sutapa’s murders happen again and again, and men in power shamelessly play the ‘victim blaming’ card, validate rape in the name of religion, it seems that Elokeshi hadn’t really died.

Perhaps, she never will.

. . .

References and bibliography:

- “Man killed partner in Delhi, dumped body pieces at 2 am for 18 days: Cops.” NDTV, 14 November 2022.

- “Shraddha murder case: charred her face to hide identity, confesses Aftab.” The Economic Times, 17 November 2022.

- “‘Waiting kor, main aa raha hu!’ Instagram profile e keno likhe rekhechhilo Susanta.” Anandabazar Patrika, 15 May 2022.

- “Shraddha Walkar murder: now, union minister blames live-in relationships for rising crimes.” MSN.com, 18 November 2022.

- Anuradha Mascarenhas. “Domestic violence cases in India increased 53% between 2001 and 2018: study.” The Indian Express, 29 April 2022.

- Bengal Sati Regulation, 1829 – Wikipedia

- Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act, 1856 – Wikipedia

- Government of India Act, 1858 – Wikipedia

- Richard Bourke, 6th Earl of Mayo – Wikipedia

- “The Special Marriage Act, 1872.” Nasir Law Site, 25 May 2015.

- “150 years of Bengali professional theatre.” KolkataTheatre.com.

- Anhik Basu. “Narichoritre purusher bodole chai nari: Madhusudan er shortei bhengechhilo Bangla theatre er songoskar.” Silly Point, 27 January 2023.

- Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar – Wikipedia

- Queen Victoria – Wikipedia

- Chandramukhi Basu – Wikipedia

- Indian National Congress – Wikipedia

- Sanjoy Ghose. “The Tarakeshwar Case: when the “theatre” in the court room was more interesting than Shakespeare’s Othello.” Bar and Bench, 25 October 2020.

- Dipak Sengupta. “Elokeshi-Mohanto kotha – ekti fire dekha kahini o ekti andolon.” Abasar, 15 November 2015.

- Tarakeswar Affair – Wikipedia

- Geraldine Forbes. “In search of Elokeshi: the death of a young wife in Colonial India.” Readings in Bengal History: Identity Formation and Colonial Legacy, pp. 139-162, Bangladesh History Association, 8 December 2017.

- Tanika Sarkar. “Talking about scandals.” Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation, pp. 53-94, Ashoka University, 2020 (6th ed.).

- Sripantha. Mohanto-Elokeshi Sambad, Ananda Publishers, 1984.

- Aajkar Bajar Bhau – an anonymously written and published play preserved by British Library.

- Olivia Majumdar. “Notes on a scandal.” British Library.

- Indrajit Hazra. “Elokeshi’s sojourn: the woman is always at fault.” The Sunday Guardian, 11 March 2016.

- Ajantrik. “Lewis’s Royal Lyceum.” Purono Kolkata, 10 July 2021.

- Ajantrik. “The last of the English theatres in Colonial Calcutta.” Purono Kolkata, 7 December 2021.

- Kalighat Paintings – Wikipedia

- Kalighat Paintings and Drawings – a documentary film by Raja Mitra

- Kalighat Icons: Paintings from 19th Century Calcutta – a booklet of an exhibition held in Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

- Pritha Mukherjee. “Battala and before: the development and demise of the woodcut prints of Calcutta.” Immersive Trails, 2 July 2019.

- “Lithography: Kolkata’s woodcut artists.” The Statesman, 14 October 2017.

- Shibnath Shastri. “Ramtanu Lahiri mohashoyer jonmo, shoishob, balyodosha o Krishnanagar er todaninton samajik obostha.” Ramtanu Lahiri o Totkalin Bongo Somaj, pp. 22-41, S. K. Lahiri and Co. 1909.

- Brajendranath Bandyopadhyay. “Dhormosthaan.” Sangbadpatre Sekaler Kotha, pp. 266-271, Bongiyo Sahitya Parishad, 1971 (4th ed.).

- Swati Chattopadhyay. “Representing sexual transgression.” Representing Calcutta: Modernity, Nationalism, and the Colonial Uncanny, pp. 229-237, Routlege, 2005.