Let’s talk about the 19th century. The imperial powers of Europe have impending ventures of colonisation that would change the face and fate of some countries forever. At the centre of this familiar but intensified imperialism was the heart of growing Christianity. Religion was seeping through and through the continent, bringing masses together. Time saw Christians unite to take shelter in Christianity, their faith, during the turmoil of Europe’s own wars and the ones abroad, to keep them sane and optimistic. Around this while, European powers set eyes on the African state to colonise for its rich, untapped resources. This is the segue to why one of the C’s of colonisation is Christianity. While it carefully held the ones of its likeness together in Europe, Christian forces destroyed the traditional African society and culture.

The role of religion in communal harmony, therefore, depends on perspective. This essay aims at exploring its impact on communal harmony, against the context of religion and what it stands for to the people.

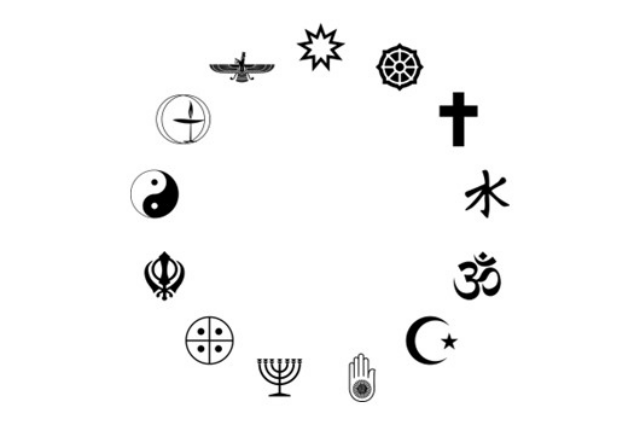

Religion finds two distinct definitions in two main schools of thought: pragmatic and substantive. Pragmatic definitions define religion as what unifies people, integrates an individual’s conscious will and unconscious drives, or provides guidance in the quest for life’s meaning. On the other hand, the substantive definition of religion calls practices and beliefs religious if it involves spiritual beings. Of the evident disparity between the two definitions, our intuitions guess that the correct form of religion surely must lie between these two schools of thought. However, something that binds these definitions together is the inevitable outcome of forming communities. The ‘pragmatic’ devotees find the hope of religion in a non-spiritual and non-diety identity, whereas the ‘substantive’ devotees find that same hope in a spiritual identity and project it to a tangible deity. Conclusively, both sects attract their kind, forming a community that believes in the same cause and thought process. When seen from the perspective of these individual communities, communal harmony is widespread. People of the same religion find a sense of belonging and social validation in shared hope. In the face of crises, intellectual or social, people take respite in their religion. Their religion promises them a right to living and the familiarity of known doctrines and practices. Every such crisis or stability tightens these individual communities, harmonising these individual cocoons of religion.

But this harmonising becomes irrelevant as soon as the definition of ‘communal’ is broadened.

By the true definition of the word communal, we get a sense of inclusivity and absoluteness. It is defined on the world community and how it breathes together every minute. So communal harmony rightfully should speculate how these communities react to collision and coexistence. This is where the positive role of religion in communal harmony becomes bleak and convenient. Religion and its people protect the sub-communities that it forms within the all-inclusive community we speak of above but is too deeply carved in stone to be accommodating. Consequently, knowing the supremacy of their ideology, they try to satisfy the greater being - fear and guilt become the drive to worship, not hope. This is when, coddled in its own convenience, religion delivers the opposite of what communal harmony is.

Mankind came up with Gods to fill the gaps in its intellect and being. Nietzche says that the aforementioned substantive religion comes from the primordial man, who needed the tangible and evident comfort, which by no means is wrong to expect of religion, to confirm their good intent and appease their guilt. Making sacrifices and offerings to the deity of those who they themselves killed was a means of salvation. From picture books of childhood, we learn that man invented Poseidon when it failed to explain waves and ocean currents. Every time nature was a riddle, man gave it a name and worshipped it because of its innate inexplicability and fear. By doing so, the man successfully segregated religion from non-religion. It explained the gaps in science and, coincidentally, became an identity of hope. This human obsession with organising all forms of existence into definable groups has pushed the limits of science and intellectual evolution. It was, is and always will be natural.

However, the meaning of hope, the beauty of a human emotion, which ultimately is what religion branches from, constricts harmony if it draws just from the substantive counterpart of religion. In the drill of segregating religion from the non-religion, it tends towards the substantive side more, whereas there has to be pragmatism in one’s following of religion, like every other aspect of life.

The pragmatic approach of religion nuances the concept. Kevin Schilbrack says in his journal article “What Isn’t Religion?”, “pragmatic definitions are not burdened with the idea that to qualify as a religion, cultural phenomena must include a belief in God or some other common reality…” The religious masses of history and today lose touch with this side of religion. The hope that is symbolised in the worship becomes convenient and transient because people refuse to believe that the reasons and answers they seek in their religion are not restricted or unique to theirs, but is available in any form of religion. The inter-community peace and consideration go absent, religious communities sustain themselves prosperously but don’t realise how they draw seismic lines along their boundaries.

The negative role of religion on communal harmony also finds its foundation in its own history. Almost every religion is built on wars in the name of peace. They have sacrificial rituals written down in their doctrines. For instance, the Muslim practice of jihad, the Christian martial images, the Ramayana and Mahabharata are named ‘dharmyudhs’. The devotees justify this as the ‘fight for good’, but the good that they talk about is a universal concept in itself, which can be realised to the fullest only if they are open to breaking down their walls of substantive ideologies.

Leigh Hunt in his poem, “Abou Ben Adhem”, explains religion in its metaphors. Hunt points out that the only true reality of life is humanity. We, humans, are brazenly aware of the mortality of life, so we cling on to hope. We find solace in hope in a religion, the promise and therapeutic nature of it - their worship, and their adherence to their divine law give them a way of life. The religious fail to understand that something as common as an act of finding optimism cannot be an absolute idea of any one religion. Communal disharmony, riots and bigotry runs in today’s world, along the lines of religion - from the Christian conversion mission of the Europeans in the 19th century to the Hindu-Muslim riots of the 21st - devotees convinced in the supremacy of their religion invalidate the purity of it.

Religion is said to serve four benefits - social relations, the body, nature and existence in general. Kevin Schilbrack says that theologists believe that every religion seeks to act wisely, properly or best. However, communal disharmony is when people consider their definition of religion as absolute. But they fail to realise, as Peter Berger said, that their definitions of religion cannot be true or false, therefore absolute, they can be more or less useful at the most. Communists may hold communism as their hope, a poet his lover and Christians regard Christ as their hope, and therefore religion. The communal disharmony is not because of the widely spread and populous definitions of religion, but because of the orthodoxy of it. Religion presents a chance to unite in the name of devotion and faith while retaining individual versions of it, which has communal harmony resting on its shoulder. Still, people are somehow yet to realise it.

"Why brought ye us from bondage,

"Our loved Egyptian night ?"

. . .

Citations:

- Schilbrack, Kevin. “What Isn’t Religion?” The Journal of Religion, vol. 93, no. 3, 2013, pp. 291–318. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/670276. Accessed 25 Nov. 2022.

- Princeton readings in Religion and Violence, Mark Juergensmeyer.